2021 has begun and of course the troubles of 2020 have come along as well for the ride. Political issues haven’t gotten any better and neither has the pandemic. However, there are glimmers of hope as well that we can begin looking forward to!

With that being said, I am excited to get started with more blogging! This first post will be about 5 common myths I have come across, mainly with more amateur genealogists who are recently beginning their research. I will try to set the record straight for some of the most common myths and where one would find information to help with their genealogical research.

1. All the records were burned!

This is a common myth I think in genealogy overall and I have come across it in Puerto Rican genealogy as well. Granted, yes “burn counties” do exist in the United States. Given events such as the civil war, some government buildings (I think mostly in the south) suffered damage that left the documentation scorched and irreplaceable. Luckily for Puerto Rico, we have not had any civil issues amongst our own citizens to this extent. The Spanish-American War did not cause a loss of vital event documentation and therefore most of the genealogical research is still traceable.

You will find that the further you go back the harder it may become, some church books have suffered damages and/or ink splotches. This however, seems more common when you start getting farther back in the 1700s (at least with the church records available online) but there definitely are documents to begin your research with for at least is a 200 year span of time – whether they are the United States Federal Census records (1910-1940 range), Puerto Rican Civil Registry (1885-present), or the Puerto Rican Catholic Church records (prior to 1885). There are of course other records such El Archivo General de Puerto Rico (AGPR) or El Archivo Diocesano de San Juan located on the island, but these generally require a bit more knowledge on how to use them and what is housed there. All other previous records mentioned are available via Ancestry ($) and FamilySearch (free, but a free account is needed).

2. No records exist for my family because they were poor

This I think is common amongst Puerto Ricans who already are second or third generation living on the mainland, who came from families that probably left just as industrialization on the island was occurring and came to places like New York to look for a better life. The stories of being poor, being illiterate (discussed more in myth #3), and coming from nothing I think transcends the idea that genealogy and records, which were kept by others and not by the family themselves. I have gotten some push back on this by people who tell me “no, you don’t understand, my family was really poor before coming here” because they know that I have had success with genealogy, but what they don’t know or realize is that my family came from a similar situation. 3 out of 4 of my grandparents were born in San Juan but 8 out of 8 of my great-grandparents and all of their families were from different and sometimes very remote parts of the islands outside of the capital. Whether it was high up in the mountains or near the southern coast where they themselves cleared mangroves to create land on which to build their homes, my family definitely did not have unlimited resources, money, and most had big families struggling to make ends meet.

Many of my ancestors came from humble people who worked the lands for many generations and the only branch that seemed to have any wealth in my family somehow lost it in the mid-1800s. So my family instead of coming straight to New York, first moved to the capital of San Juan and later to New York (only one side of my family though) and so I was born in New York, but even then, most of my family is still on the island.

Records were kept by others (in this case Puerto Rico itself) who tracked birth, marriages, and deaths whether on a civil or religious basis. Yes, it is true that our families will lack certain things such as correspondences/letters, but you can still find them on records (as listed before such as census, civil, and religious documentation). This myth flows a bit into the third one because social class and education are tied here.

3. My family was illiterate, so there are no records available

Similar to myth #2, there is a belief that just because a family was illiterate they will not exist on records. You will hear people say “my great-grandfather didn’t even know how to write his own name or when his own birthday was”, which again, I can attest to my own family. Literacy usually doesn’t effect genealogy only when it comes to finding signatures of family members or potentially ancestors that came from another country to Puerto Rico and suffered a phonetic spelling change due to the lack of knowledge of writing. So though, literacy is important, likely it will not stop your research – it may cause some bumps on the road, though!

For example, my own great-grandfather would sign an “X” or a “+” for his name – common in records used by those who didn’t know how to write and was usually not too sure of his birthday. Luckily he was given his saint’s name of the day he was born so we could confirm his birthday just with his name. Pictured below you will see any example of how men usually would “sign” their name when they did not know how to write. I knew my great-grandfather and despite his inability to sign his name, he appears on records such as the census record, civil birth registration, and his WWII draft registration card. My great-grandmother’s baptism record even mentions their marriage which occurred many years later and in San Juan, while she was born in Yabucoa, Puerto Rico.

Another possibility like I stated above is that your ancestor’s name underwent some type of change – in the United States there is a myth that surnames of immigrants were changed when they arrived to Ellis Island, however further research has proved that to be mostly incorrect or overstated. These two articles do a good job of explaining the actual situation:

- “Why Your Family Name Was Not Changed at Ellis Island (and One That Was)” (NYPL)

- “Why Your Family Name Did Not Come From a Mistake at Ellis Island” (MentalFloss)

Granted, in Puerto Rico I have seen names change overtime and I’m not sure exactly “who is to blame”. You see names such as Morfi and Soliván which are said to have at one point been “Murphy” and “Sullivan” before they became more Spanish sounding/spelled surnames. Others include French, German, or Italian surnames that underwent slight changes while on the island. My own 4th great-grandparents are examples of this.

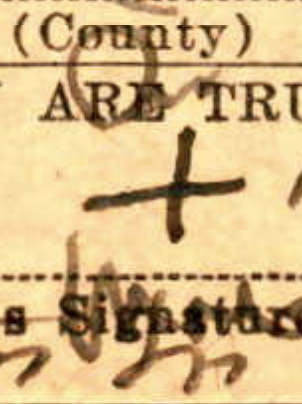

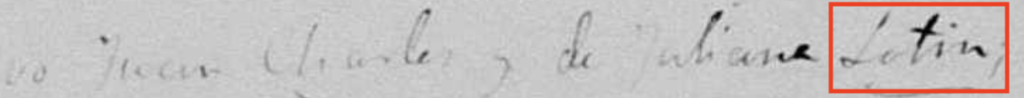

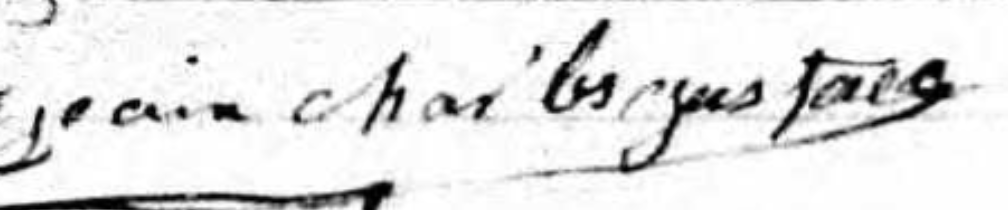

My 4th great-grandfather who was from Guadeloupe would go back and forth between “Gustave” and Gustavo” on records, though he signed using the French surname (so he was aware of the spelling) while my 4th great-grandmother from Martinique first appears as “Lautin” in her marriage record but later the name warped to “Lotten” and other similar variants. They married and lived on the island of Vieques that did have a French influence/migration so I wonder if that helped preserve the “Lautin” spelling for a while. Yet in Salinas, Puerto Rico where the family later moved, the surname was changed to “Lotten/Lotin”, possibly due to her lack of knowledge with writing. In the images below you will see however that the use of Lautin (original surname) and Lotin (warpped version) were both used even in the same year in the same town! So there isn’t a method to this madness that I can explain.

4. There was no church/registry in town, so they were not recorded

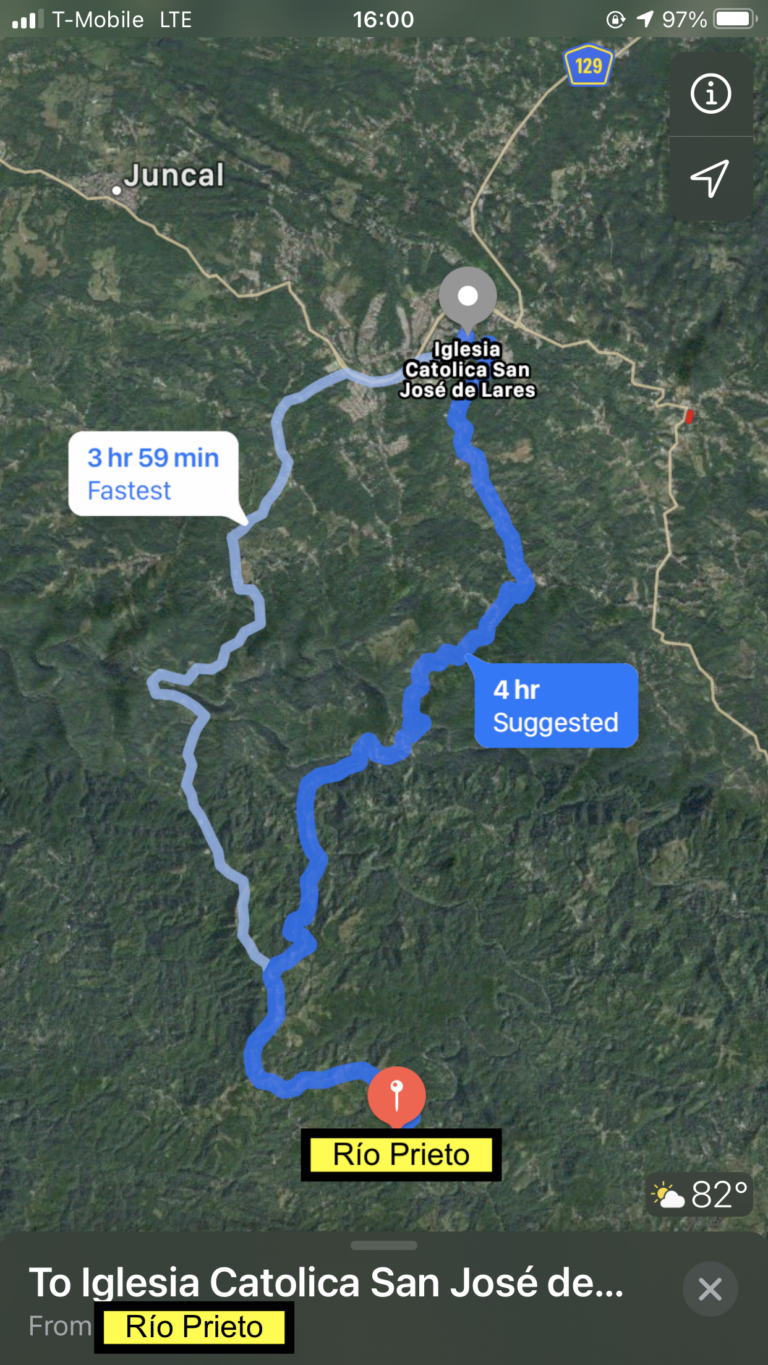

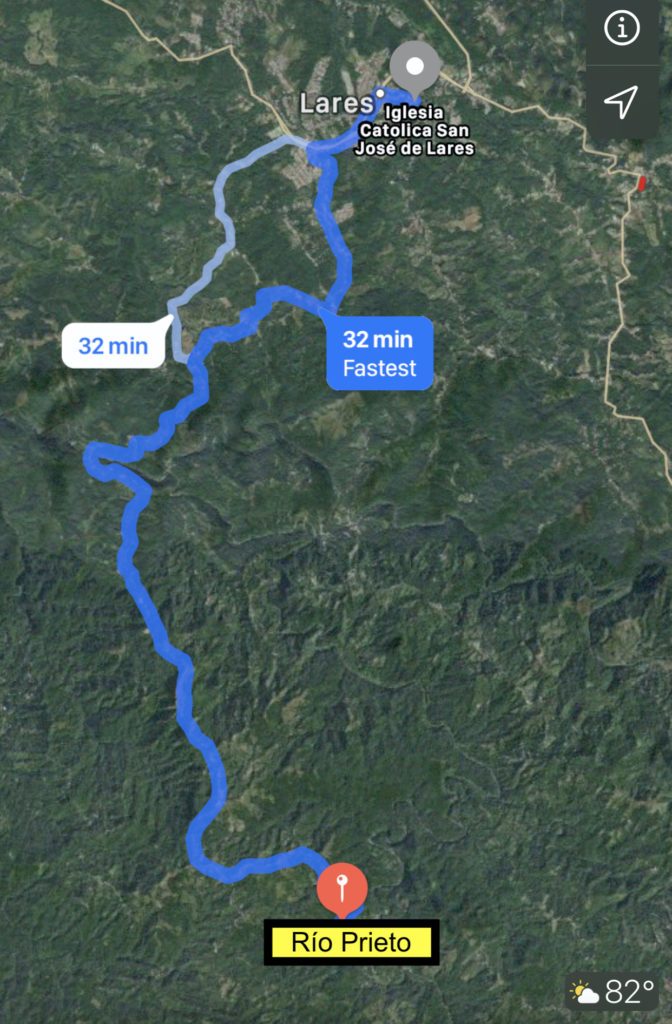

This myth is tied to the idea that because a certain ancestor lived in a remote part of Puerto Rico that they flew under the radar for many years and they were never recorded. Similarly to myth #2, despite our families being illiterate or living in remote parts of towns on the island, they more often than not were registered. I don’t think I have come across a modern day (1800s-present) example of someone I have researched and have come up empty-handed for them with absolutely no records. There is always some type of record to be found, whether it be a birth, marriage, or death. Granted, you will see “inconsistencies” such as illegitimate child who you might have thought were legitimate, uses of middle name instead of first and middle names, and even flip-flopping between surnames or spellings (as mentioned above with Gustave/Gustavo and Lautin/Lotten), but I think this speaks more to the reality of their time (literacy being one of them) versus some type of governmental evasion. A perfect example is my family from Lares, they live up in Río Prieto, a barrio in Lares with very narrow and curvy roads, still to this day. However, all my ancestors that I have researched in Lares have been registered, my 2nd-great grandfather’s land is still there and located in a remote part of the town. To give you an idea, I have taken two screenshots of how long it would take to get from his land to the Iglesia Católica San José in the downtown area of Lares, which is where the town’s church is located. Again, though Río Prieto had no branch of the church (at least that I am aware of) all of my ancestors were baptized, married, and died appearing on civil records (Lares church records are not available online currently). My 2nd great-grandfather even left behind his land in a will!

Likely, though families did not appear constantly in church to make registrations whenever something occurred, either two things possibly happened: (1) a traveling priest would come to the town and make registrations for newly born children and/or, (2) families would go down to the church when they could and register various events. Somehow though, it got done!

Below you see two options of how to get to La Iglesia Católica San José on foot (4 hours!) and by car (32 mins). I imagine by horse would be somewhere in between but remember that these are curvy roads up/down to Río Prieto.

5. My family wasn't religious, so there are no records for them

Finally, myth #5! This myth does not come up too often in conversations, but I have heard people mention it to me as to why they can’t find their ancestors. Now, there is a possibility that your ancestors weren’t super Catholic or practiced/celebrated the religion outwardly and openly. However, I think it is important to acknowledge the pressure of this religion (the main one for many centuries) on the island and the idea of fitting into a certain “mold” of what a Puerto Rican family was. Today, there is more diversity in regards to religion, identity, etc. but consider the societal pressure of the 1700-1800s of remote, small towns where everyone knew everyone and were mainly Catholic. There likely was an undeniable pressure to “perform” to some extent, whether it was just baptizing and marrying under the church for societal sake but not attending mass religiously. This is an area I am not well versed in and would love to read more about and how Catholicism as an institution normalized certain behaviors on the island. There are of course various influences on the island such as indigenous/native ideologies, African enslaved influenced Santería beliefs, and the idea of a Sephardic Jewish presence that remained until recently very, very under the radar. However, coupled with the overwhelming power of the Catholic church – what would these interactions have looked like over a 300+ year Catholic-normative life?

Nonetheless, the church before 1885 was responsible for tracking vital events on the island and I am not sure if there was a “welp, I guess we have to do this…” feeling. I am not sure within my own family if there was a religious pushback but it seems my family wasn’t super Catholic as a whole. My own maternal grandmother tells me that it was her decision to be more religious, whereas her parents only attended mass on important events such as Easter/Christmas and my great-grandfather though a “religious” man in the home never attended mass with them.

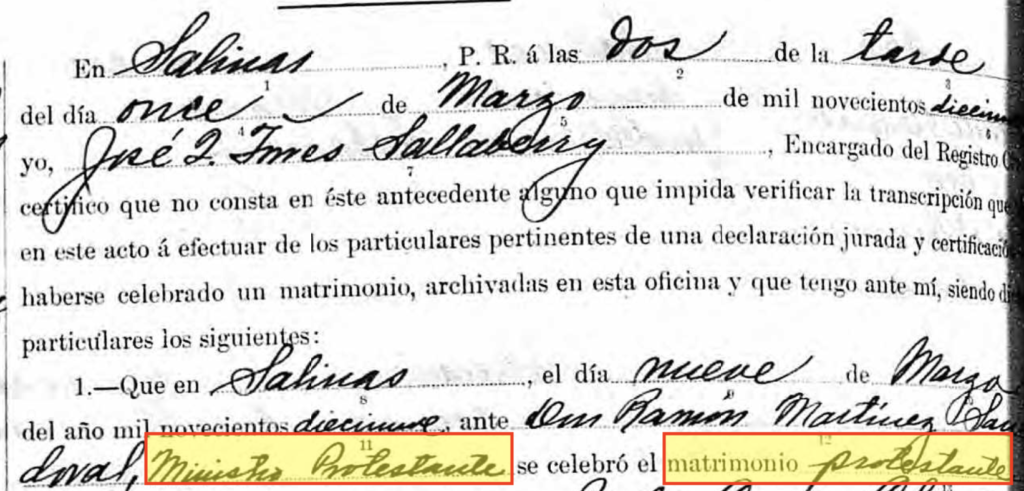

Only recently did I notice for example that a pair of 2nd great-grandparents married in Salinas, Puerto Rico in 1919 as protestants, despite their ancestors’ vital events and even their own baptisms occurring within the Catholic church – so I would imagine they made this choice on their own, they being in their mid-20s at the time. This might explain why I can not find my great-grandfather’s baptism record in the Catholic church, even though I found his civil birth record.

So though your family might have not outwardly celebrated Catholicism, pre-1885 was mainly controlled by the church and alternative options to register your children were not bountiful. Once the Registro Civil de Puerto Rico was established and began tracking vital events in 1885, this was a way to be registered without the influence of the church. However, you will still see two sets of records for many of your ancestors, for examples: 1 civil birth record, 1 baptism record; 1 civil marriage, 1 religious marriage; 1 civil death, 1 religious death. And it was thanks to this that I realized a mistaken was made on the civil death of my ancestor while naming his parents which were named correctly on his religious death record!

Below is an excerpt of the 1919 marriage which shows it occurred as a “protestant marriage”, sometimes you will even see matrimonio civil – civil marriage on marriages occurring post-1885.

I hope this helps clarify some of the myths we’ve heard about Puerto Rican genealogy and opens up the possibility to continue research your ancestors!