Back in January 2023 when I lived in France I got a chance to visit the ANOM (Archives Nationales d’Outre-Mer). This was exciting because though I had already done research on the ANOM website, I had never been there in person. Their website includes birth, marriage, and death records for my enslaved ancestors from both Martinique and Guadeloupe, dating back to the 1800s. There are earlier records for both islands; however, my ancestors were not present there (Martinique) or were enslaved and therefore don’t appear amongst the white and free population (Guadeloupe).

The actual brick-and-mortar archive is located in Aix-en-Provence, France and since I lived in Lyon I was not too far off. So I arranged a BlaBla Car (ride share service) and went on one of my days off to visit and do some research on my ancestors from the French Caribbean.

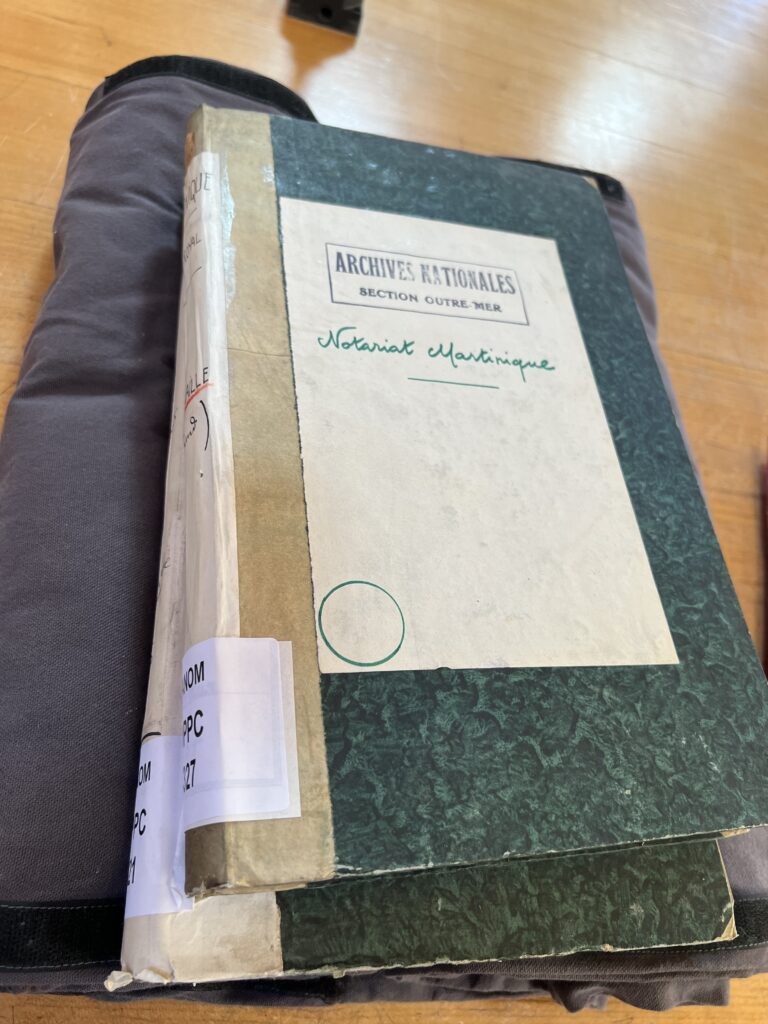

I wanted to mainly explore documents related to my ancestors in Martinique because this was the best option I had in finding something seeing as how I already knew a bit about when my ancestor Eglantine Lautin was purchased. When I went in I left my belongings downstairs and signed up for a visitor’s card. This would allow me to return and swipe in the next time I would decide to visit. After going upstairs I spoke to the archivist about looking for records and they led me to a computer where I could search what files were available there by searching for various names – this in turn lead me to find the name of the notary associated with the acts. Not only did I search for the names of my ancestors (which really didn’t show up) but also the names of the people who owned my ancestors since likely they would be the ones leaving behind transactions through the notarial records in Martinique. Having identified a few names, I request the records and sat as I waited for the books. You’re only allowed to see a certain number at a time and they can be requested every 30 mins (if I am remembering correctly). So I patiently waited in the reading room and hoped that I would find some interesting records.

It is important to note that I did not know the original purchase date of my ancestor Eglantine Lautin, my 5th great-grandmother from Africa. By searching the notarial records I hoped to learn more about the transactions that occurred between the Garnier Laroche, Lapierre, and Le Terrier families to see how early on Eglantine might appear in records. Though Louis Le Terrier did not own my family, he owned land that the enslavers would ultimately purchase and use as a part of the coffee plantation.

Holding these old records was very exciting and the thought of being able to trace my family further back (albeit it through their enslavers) was a bit surreal. I searched through a few of the notarial books that I identified through their website in search of Eglantine; however, I ultimately was not able to find out more information about her. Though I was initially bummed, I made sure to take pictures of the documents I did find tied to the aforementioned families. Having these records would help me to establish a clearer timeline as to how each of then were related and when they got involved in the slave trade. Here are some discoveries below.

1 February 1790

Jean François Garnier Laroche married Louise Françoise Ozier on 1 February 1790 and they appeared before a notary in Rivière Pilote to draft up a marriage contract. Finding this document provided some more context to the Garnier Laroche family and the lives they lived in the late 18th century.

Some of the things I learned from the document:

- Jean François was already in possession of a cotton and coffee plantation which included 8 “squares” (quarrés) of land, four enslaved individuals, and one horse.

- The bride’s mother presented her with a nègre nommé Noël criol de vingt-deux ans (a black creole enslaved man named Noël who was 22 years old).

- The bride, Louise, brought with her into the marriage Victoire, négresse criole de 15 ans estimée – 2000 livres (Victoire, black creole woman, 15 years old, estimated at 2,000 livres).

Though we are not provided the names of the enslaved individuals that Jean François was bringing into the marriage already on his plantation, we learned the name of two individuals (Noël and Victoire), both fairly young and belonging to the Ozier family. Both were referred to as criol/criole (likely to creole) which means that they would have been born in Martinique. It is possible that an earlier transaction might identified the four enslaved individuals held by the Garnier Laroche family.

6 August 1824

Louis Le Terrier, officier d’infanterie de La Garde nationales au sixième bataillon (Infantry officer of the National Guard in the sixth battalion) and his wife Jeanne Catherine Depaz sold land to Pierre Victor Eustache, Pierre was referred to as a homme libre likely meaning that he was a man of color that had either been born into freedom or had received his freedom earlier on. This transaction took place in Rivière Salée, Martinique where my 4th great-grandmother was born and enslaved. It seems that Louis Le Terrier had this land since at least 1819.

16 March 1825

This last record showed that Jean Jacques Catherine Lapierre, resident of Saint Esprit sold land to Dominique de Pellerin, écuyer (squire), and was also a resident of Saint Esprit.

Jean Jacques Catherine Lapierre was the father of Rose Hélène Lapierre who along with her husband, Jean François Marie Joseph Garnier Laroche, would end up acquiring my ancestor in 1846.

Future Research

Since I only had one day to do research in the archives, I imagine there is still much to explore that I was not able to see. Finding these records allowed me to see that both families (the Garnier Laroche and the Lapierre) were involved with plantation life and slavery before the arrival of my ancestor. Understanding these records, though not directly tied to my ancestor can help me to better understand the people that would control and oversee her life in Martinique and that of her children.

It is very possible that I might not ever get a chance to find out how my ancestor originally arrived to Martinique and more information about her via French records, but my hope is that through other forms of research such as DNA (specifically mitochondrial DNA) I may be able to better understand Eglantine’s origins. It is my hope this year to better understand the maternal legacy my ancestor left behind in Puerto Rico and to try and find a direct descendant that may be able to help provide us a maternal haplogroup in an attempt to better understand Eglantine’s origins in Africa.

Similarly, I hope that most of the notary records make their way online sometime in the near future. That way I won’t have to travel to southern France again to conduct research in the ANOM, though it was a cool experience going in person and learning more about my ancestor’s life in Martinique.