During the month of June (my last month of living abroad), I was able to visit Andalucía in southern Spain to continue researching my Dávila family that came from San Juan del Puerto. During my time there, I came across a marriage record between my 8th great-grandparents that showed them entering into a consanguineous marriage. This meant that I could find more information about their wedding in the archives of the Obispado de Huelva.

So let’s dive into what I found while researching my ancestors there.

Arriving to Andalucía

I wanted to visit Andalucía again after my first visit way back in 2019 and it was one of my genealogical goals for 2024! There was still much research to do and given the pandemic and life in general, I had not been able to return. So I made it my goal to return before leaving Spain! After some phone calls and booking my train and hotel, I was off to San Juan del Puerto for 4 days to get some research done. This time I decided to stay in the town of San Juan del Puerto itself so as to not waste time going and coming back from Huelva. I did notice, however, that the train station was functioning this time so getting into San Juan del Puerto was much easier since I now had various train and bus options, but in the end I enjoyed staying in the town and it made research that much easier for me.

Researching in San Juan

del Puerto

I spent mostly my evenings visiting the church in San Juan del Puerto to get my research done. I would spend about 2-3 hours each day pouring over the records and taking notes to the best of my ability of what I found, where I found it, and any negative findings. That goes without saying – researching can be fairly mentally taxing! Between juggling different names, dates, handwritings, and problem solving on the go (wait, this book isn’t available… how can I find out more?) I would get back to the hotel fairly tired and still have to work another 2-3 hours to process what I had found, what theories did or did not make sense, and make my “grocery list” of ancestors I wanted to research next. All in all, I had a great experience researching and I wish I just had more time to go through everything much slower!

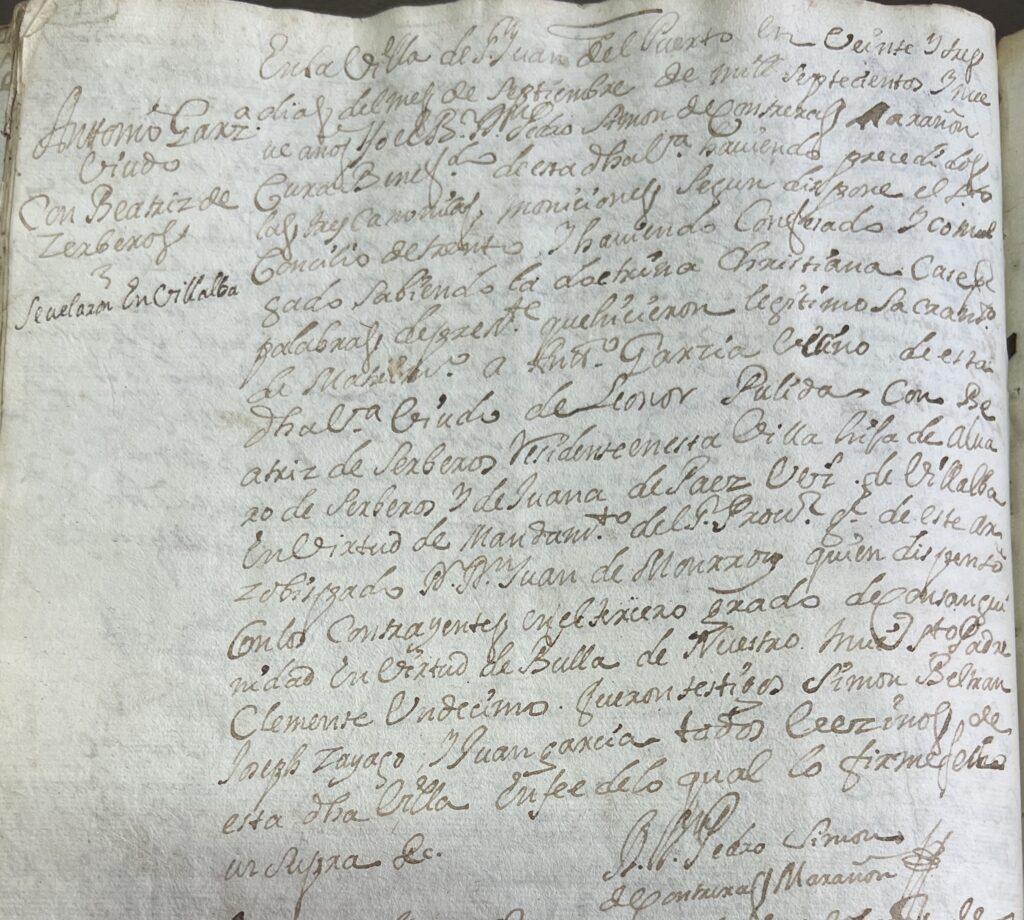

During one of these sessions I was finally able to break through a brick wall! The first time I went to research in 2019, I had learned the name of my 7th great-grandmother, Juana García de Serberos – but in every other attempt to research her and her parents, I found nothing. This time I was able to find a marriage record for her parents which proved extremely helpful in learning more about them! Juana was the daughter of Antonio García and Beatriz de Serberos, though I am unable to find her baptism record given a missing chunk of baptismal records, I was able to find her parents’ marriage in 1709. Below, after the image, is part of the transcription and translation.

<ESPAÑOL>

En la villa de San Juan del Puerto en veinte y tres días del mes de septiembre de mil setecientos y nueve años… Antonio García [¿vecino?] de esta dicha villa, viudo de Leonor Pulida con Beatriz de Serberos residente en esta villa, hija de Álvaro de Serberos y de Juana de Páez, vecinos de Villalba… Juan de [¿Monrroy?] quien dispensó con los contrayentes en el tercero grado de consanguinidad…nota: se velaron en Villalba.

<ENGLISH>

In the town of San Juan del Puerto on the 23rd day of the month of September in 1709… Antonio García [neighbor] of this said town, widower of Leonor Pulida with Beatriz de Serberos, resident of this town, daughter of Álvaro de Serberos and Juana de Páez, residents of Villalba… Juan de [Monrroy?] who dispensed with the contracting parties in the three degree of consanguinity… note: the veiling ceremony took place in Villalba.

From the marriage we can learn a few things:

- Beatriz de Serberos was likely not from San Juan del Puerto. Usually I see residents listed as vecinos (neighbors) of the town except here Beatriz is listed as a residente (resident).

- Antonio García was a widower of Leonor Pulida and this was actually his second marriage. His first marriage could have either occurred in Villalba or San Juan del Puerto Rico. Researching backwards from 1709 in San Juan del Puerto would confirm whether or not it occurred in that town.

- Antonio García and Beatriz de Serberos were actually cousins which is why they needed permission from the church to marry in the 3rd degree of consanguinity. This would mean that their relationship was around their great-grandparents’ generation.

- The veiling ceremony took place in Villalba. This small note would ultimately be very helpful while researching in the Obispado de Huelva.

Researching further I was able to find Antonio’s first marriage to Leonor Pulida; it occurred in 1697 in San Juan del Puerto. Here, Antonio’s parents were listed – Juan García and Margarita de Herrera. Below we can see what the family tree would start to look like.

However, notice that none of the surnames so far are matching up. This is one of the biggest problems of 17th century Spanish genealogy – surnames were not fixed! This means that sometimes ancestors chose surnames for their offspring based on popularity/status. Different siblings also could carry different surnames themselves, which complicates the search even further.

When I noticed that the couple entered into a consanguineous relationship, I asked the volunteer at the church of San Juan Bautista whether I could find out more information about them. The records permitting them to marry were likely still located in the Obispado de Huelva de volunteer told me. Since I had mornings available I would try and go before I left in order to find out more information about Antonio García and Beatriz de Serberos. This was also my only chance because Villalba, better known as Villalba del Alcor, lost all of their records before the 1930s due to the Civil War. This meant that all of the church records that would contain more information on my family were gone forever…

The Obispado de Huelva was my only hope!

Obispado de Huelva

Located in, you guessed it… Huelva, I headed there Thursday morning since they were going to close early on Friday. I went with one specific goal in mind – to find Antonio García and Beatriz de Serberos’ marriage permission. I had called that morning before heading out and was told that it should be with them because they had the year in question I was searching for. I went with such determination that I even forgot to take a photo of the archive from the outside. However, thanks to Google Maps you can see what the outside looks like, quite a beautiful building!

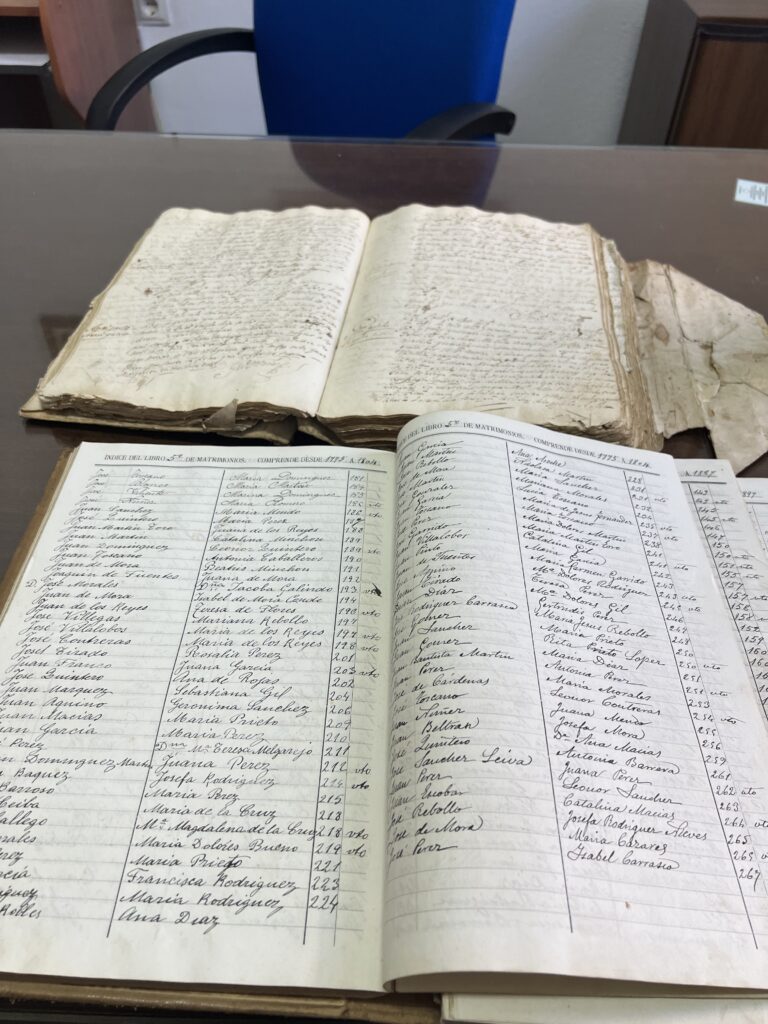

I was greeted very warmly by everyone I encountered that day and it was one of the smoothest archive visits I have had to date. I am not sure if they have more records that could be of use to me, but I would definitely return again if I needed to. Though the office space is small, they were very attentive to my genealogical questions and very determined in helping me find what I was looking for. Lucky for me, there were indexes for these marriages and so first I checked San Juan del Puerto where marriage occurred. I came back empty-handed, but found other surnames that were of interest that I would go back to. I told the archivist that I wanted to check Villalba because this was where their veiling ceremony had occurred. She was not sure that it would be there, but we had nothing to lose. Lo and behold, the record was there!

Permission to marry

Finding the permission was fairly easy because of the index the archivist provided. I was also surprised to see that the previous entry to Antonio García and Beatriz de Sebreros was a Simón de Sebreros marrying an Ana García – they would turn out to be brother and sister to both Beatriz and Antonio, respectively. Unfortunately, because the archivist dealt with pulling the records, I am not sure what boxes or legajos these documents came from and so I can not cite them correctly. I wanted to ask if she could provide me that information but since I was so pressed for time I figured I might be able to find that on a list somewhere else online and did not want to lose time.

Below, you can see the cover page for the marry permission which included 24 other pages of information, testaments, etc. to approve their marriage. Unfortunately, many of the pages were just repeating the same information over and over so it was not as enlightening as I wanted, but alas, beggars can’t be choosers!

Photo permission courtesy of Obispado de Huelva.

With the information provided I was able to trace out the various generations for the family and tie them back together. Ultimately, the tree goes back to two sisters, Paula Herrera and María Esquivel (here we can see they inherited different last names) – unfortunately, we do not learn who they are daughters to… and given Villalba’s record loss we might never come to learn their names.

What is a bit bizarre and mind-blowing to think about is that if we averaged 20 years for each generation and counted backwards, the timeline would look roughly like this.

- Antonio García Herrera, b. 1677

- Margarita Herrera/Rodríguez b. abt. 1657

- Paula Herrera, b. abt. 1637

- Parent #1/#2, b. abt. 1617

This means that the family tree would be closer to the early 1600s when Parent #1 and Parent #2’s generation was born – which is fairly crazy to think about. Their parents would have been from the 1500s!

Conclusions

Despite Villalba del Alcor having lost records prior to the 20th century, we are fortunate that some of the records were kept elsewhere and thus preserved. Without these records, I would have learned to what degree Antonio García and Beatriz de Serberos were related but not through which branch. As previously stated, I would have not known which branch to focus on either given that I was researching a time period where surnames were not standardized.

This is why preserving records is important! We can learn more about the relationships our ancestors had and tie branches together and “non-traditional” records such as these can provide us a glimpse into familial relationships typically not recorded in vital records. I am eternally grateful to the Obispado de Huelva and hope that they have other records in their collection that can be of help to me as I trace back my southern Spanish ancestors.

Do you have consanguinity on your tree?

Cover Photo: “Obispado de Huelva,” Google Maps (https://maps.app.goo.gl/eC2QSW2B9Dj1rSHU6 : accessed 9 August 2023)