In the past, I have written two posts about my family pedigree from different angles. The first was a look at colorized pedigree where I marked in various colors the towns of origins of my ancestors, clustering them by town and generation. My second post was about my family tree but from the perspective of death (a bit morbid, I know) but it was an interesting experiment where I was able to observe or find trends in my family tree related to overall family health in correlation to death. By looking at my family tree from various angles, it allows me to get to know my pedigree and ancestors in different ways. This time I wanted to focus on my family tree but based on the etymological origins of the surnames. As a genealogical and linguistic nerd, I thought this would be a great activity in learning more about the origin of my ancestors’ surnames and the various meanings they carry. This is an activity I have done in the past with my former students where they look at the origin of their names and surnames; it was always interesting to hear the various names and definitions and where some names overlapped in meaning despite not modernly looking the same! For example, my name Luis (Lewis, Louis in English) is related to the names “Ludovicus”, “Ludwig”, and “Lodewijk” – all three names that seem much more closely related to one another in comparison to the name Luis.

So let us take a look at the history of surnames and some of the ones in my family tree!

Quick History of Surnames

Depending on your culture, a surname might be something extremely old or relatively new to your ancestors. For example, some Ashkenazi Jews took on surnames much later in history (1700-1800s) compared to for example the Spanish Sephardic Jews (1000-1100) given their country’s rules on the use of surnames. However, in modern history many of us are aware of and understand the use of surnames.

However, not every country uses them the same. There is the “son of…” -son/sen and “daughter of…” -dóttir/dotter/datter common in the Scandinavian countries where the child’s gender will dictate what version of a surname a child will receive. Similarly, in Russia you might see ‘-skij’ (-ский) and -skaya (-ская) for adjective ending surnames where the former is used for males and the latter for females.

How far do surnames go back? Well again, this will depend on your culture. Research online says that China has been using surnames since at least third millennium BC when the Yellow Emperor ordered his people to take on hereditary family names. According to Chinese legend, the practice goes back to Emperor Fu Xi (伏羲) in the year 2000BC.

Similarly, in the west we are used to surnames being used after our first names, however surnames in some eastern countries, such China, Korea, and Japan, they come first. This is said to be because family is of more importance than one’s own name. So for example, famous NBA basketball player Yao Ming (姚明) is constantly referred to his surname “Yao” and not his first name “Ming”. If you asked a person not aware of this Chinese custom, they will likely tell you the opposite (that his first name is Yao and his last name is Ming).

On the other hand, the Roman empire began its use of surnames around 650BC, where the use of a “nomen” identified group kinship. In England, it is said that surnames date back to the Norman Conquest of 1086, in preparation of the Domesday Book (also known as the ‘Great Survey’).

Surnames also were sometimes physical/personal characteristics (tall, short, thin, etc.) , professions (English- Baker, German-Bäcker, and Spanish- Panadero) and even patronymics (son of…) as we have seen in the Scandinavian countries, also fairly common with Spanish surnames (Álvarez – son of Álvaro, González – son of Gonzalo). This last one a practice picked up after the Visigothic invasion of Spain.

There is definitely much more to the use and history of surnames and the topic can get veryyyy granular depending on your culture and the way are used, but let’s take a look at Spanish surnames specifically since that is where many of my surnames originate from.

The use of surnames in Spain

One of the biggest curiosities of Spanish surnames (both in Spain and around Latin America) is the common use of both surnames. There are still however some misconceptions around this practice! In popular culture you might hear people take stabs at this practice by saying: “His name is Juan de la Cruz Pérez Sánchez Santiago Hernández”; throwing together multiple surnames and forming a Frankenstein of a name! However, this is general (and I would argue 99% of the time, not the case). Many Hispanics carry only two surnames (unless one if these is already a compound surname).

For example, take my 2nd great-grandfather José Avilés Magraner. He has two surnames “Avilés” and “Magraner”. Technically, his first surname should reflect his father’s surname and the second surname that of his mother’s. However, when he was born, José was only born as an “Avilés” meaning he was born out of wedlock and not allowed to take his father’s surname. Had he been born to two married parents then his name would have been “José Magraner (father’s surname) Avilés (mother’s surname).

Why mention him as an example? Well, it goes to show you that not everything is what it seems. Some surnames we have inherited from maternal ancestors given the child being born out of wedlock. Similarly other social situations might impact a child’s surname inheritance such as Esposito, Blanco, and Iglesias – apparently, surnames given to children we had been given up for adoption.

Finally, it is also important to note that surnames in Spain did not take on this fashion of father’s, then mother’s probably until the 17th if not the 18th century. While researching my Dávila family from San Juan del Puerto in Andalucía, Spain – I noticed that the family took Dávila even though they technically should have been “de Cantos”. In those times one could choose their surname, even that of a grandparent if it meant it had more status.

Let’s take a look at my 5th great-grandmother’s name down below! It’s definitely quite a mouthful!

My 5th great-grandmother’s name was María de los Reyes Pérez de la Cruz Sánchez. Let’s breakdown her name:

Given Name: María de los Reyes

Father’s Surname: Pérez de la Cruz

Mother’s Surname: Sánchez

As we can see, she had quite a long given name and a long paternal surname to boot! Her father’s family carried “Pérez de la Cruz” for a few generations including María, but by the next generation the surname was simply shorted to “Pérez”. I am not sure where this surname originated from yet, but so far my oldest “Pérez de la Cruz” ancestor is her grandfather Simón Pérez de la Cruz who apparently was from Aguada, Puerto Rico.

Another thing you will notice is the use of “y”. In many records in Puerto Rico (such as the census or on certain civil records) you will notice the use of “y” between two surnames. This is something I still use on my tree despite the use having fallen out of fashion, given that it is much easier to visually see where one surname ends and the other beings. This is especially important when you are dealing with surnames that have “de la” in them!

The use of two surnames in my opinion is an awesome cultural feature. It allows both families to be honored without the woman having to lose her surname. In modern day Spain, you can actually choose which surname goes first which I think is a nice modernization! However, many people still use the traditional (first) father’s surname (second) mother’s surname when naming their children.

Surnames Post-Colonization

Puerto Rico’s use of surnames (along with many New World countries) is fairly complex. I say this because though we employ the Spanish surname system, many of these surnames where forcefully given to the native Taíno population as well as the enslaved Africans who were brought over. Thus, many Spanish surnames appear being passed down from slave owners to their enslaved workers or similarly early on in Puerto Rico’s history the Taíno at some adopted Spanish surnames when they began to mix (whether forcefully or willing is another question) with the Spanish population. Unlike other countries in Latin America, Puerto Rico does not preserve any indigenous surnames (likely our native people did not use surnames in their culture, especially given that it was a culture focused more on oral traditions and practices on a small island instead of a written one).

I mention this because as DNA and genetic genealogy begin to take up a huge space in the world of conventional genealogy, many people are coming to terms that they are not “enter surname here” related given various reasons like the ones mentioned above: being born out of wedlock, surnames passed on by slave owners, etc.). I have various of these situations in my own family where we do not know where the family originates from and the surname is of no help given the reasons already aforementioned.

So let us take a look at some of the surnames I have in my family tree and what they mean!

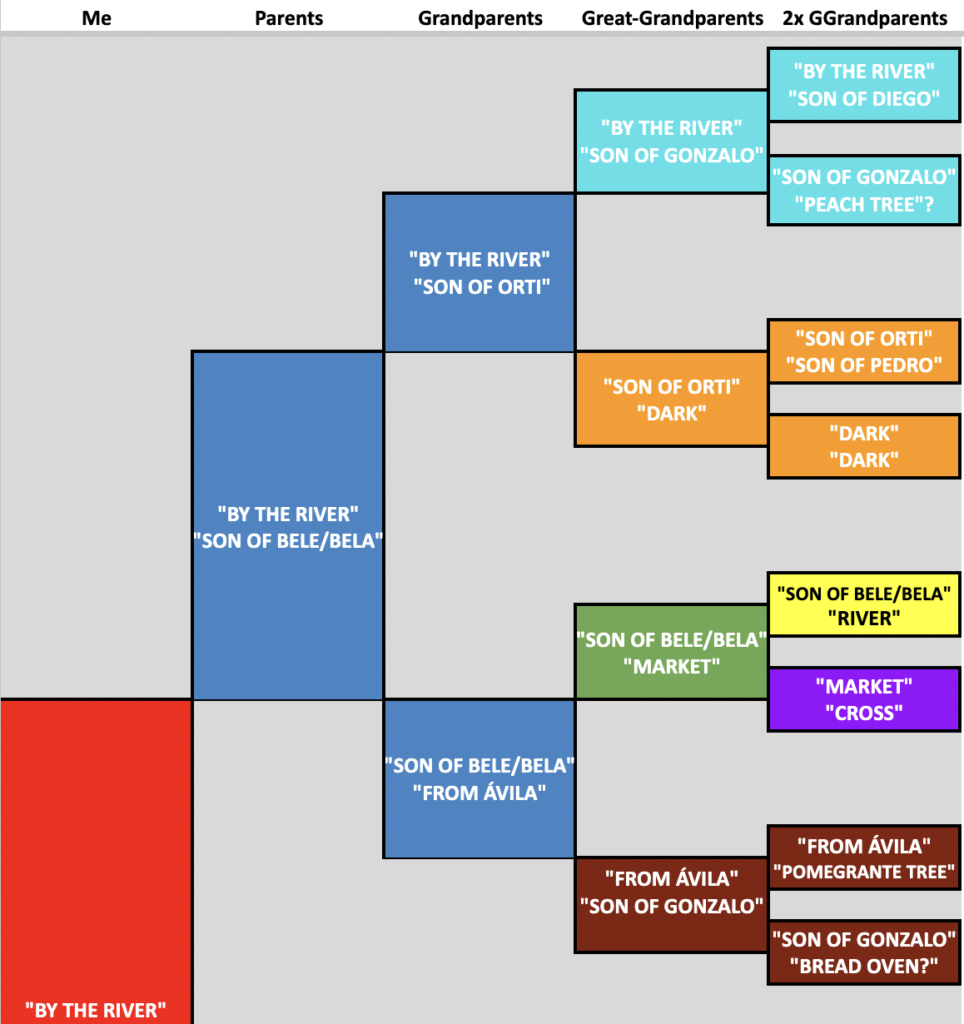

Paternal Surnames

In the picture above you can see a mix of surnames some dealing with natural objects (trees, river), two with places/towns (market, Ávila), descriptions (dark), and Visigothic influenced surnames (son of…). What’s interesting is that this is probably the most common in my tree (son of Gonzalo, Bele/Bela, Orti, Pedro, Diego)!

The surnames with question marks are surnames that have some debate about to their actual origin – the one listed is the most common to appear but there is still some debate on whether that theory is full accepted or not.

The Power of Y-DNA

I have already talked a bit about the new frontier of genetic genealogy and specifically there is one aspect that is very interesting, which is the use of Y-DNA testing in regards to male-carried surnames. Though mtDNA also is possible, since many societies are not matrilineal we end up quickly losing the surname amongst women in each passing generation. However with men, most surnames have been inherited (almost untouched in some families) for various generations and across hundreds of years.

I have attempted to use Y-DNA to find our more about various of my family lines, and I have found out a bit (not enough as I’d like to yet) from testing. Amongst them are:

RIVERA – Connected to Europe but does not match yet many of the Rivera members in Toa Alta, Puerto Rico. Possibly from another smaller branch or not originally a Rivera line.

CORREA – Likely to be of Sephardic origin, not sure from where yet as the paper trail dies in the 1700s.

MAGRANER – Typical “R” haplogroup European line, not many matches yet, none from Mallorca yet.

CHARLES/JEAN-CHARLES – Connected to Europe, meaning that the first ancestor was like a French male on the island of Terre-de-Bas, Guadeloupe to have an intermixed relationship.

Despite not finding out much right away about my Y-DNA tested lines, I think it was money well spent. This is definitely one of the lesser known sides of genetic testing and also one of the sides that still carries a hefty price. Those two pieces combined cause for less testees to appear on your list and might cause you to seek out other men in your line to beef up your test results and branches a bit.

Maternal Surnames

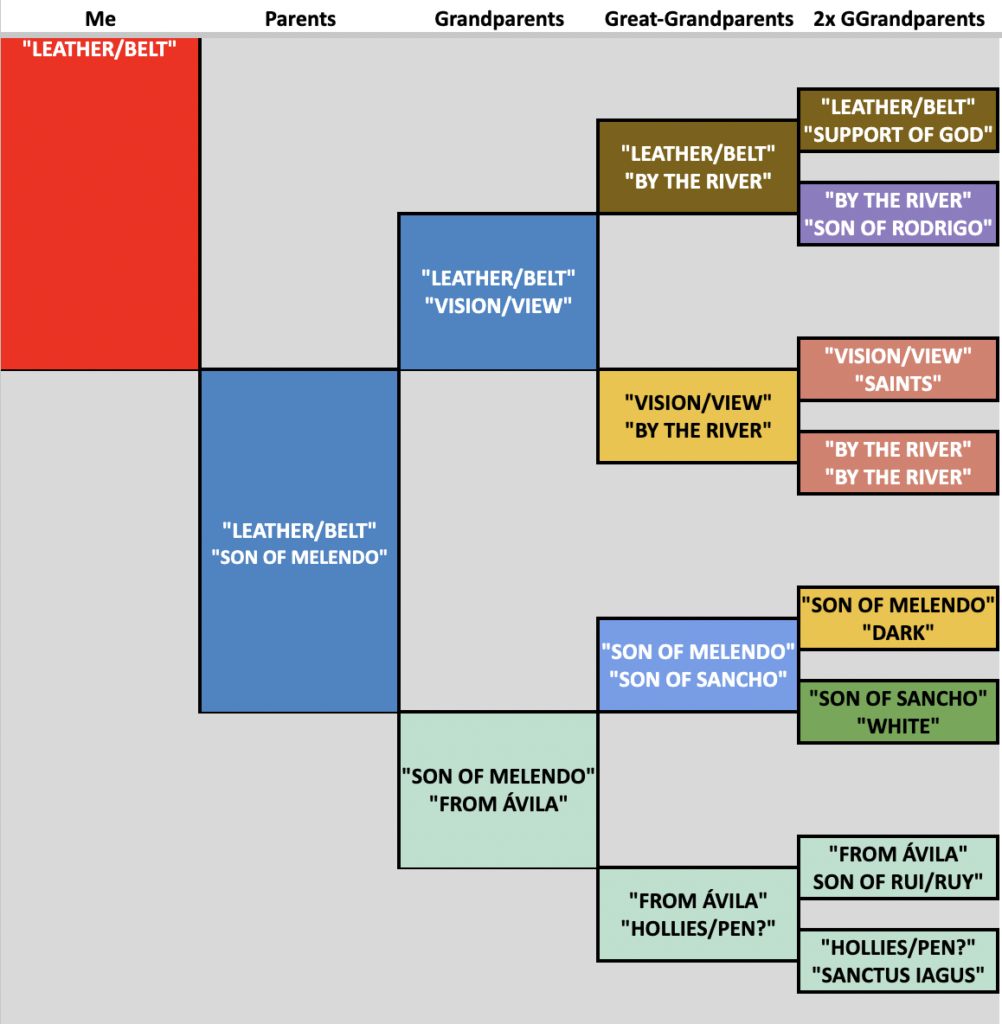

Here are some of the surnames tied to my mother’s side of the family! Similarly, you can see a mix of surnames. Interestingly, there are a few tied to God/religion on this side (“support of God”, “Saints”, and “Sanctus Iagus”) and also a mix of patronymic style surnames (Son of Rodrigo, Melendo, Sancho, Rui/Ruy). What’s interesting is that the surname related to “from Ávila” on my mother’s side of the tree is not the same one on my father’s side of the tree.

Power of mtDNA testing

Similarly, thanks to mtDNA testing I have been able to learn about the maternal haplogroups in my family tree. I have yet to test one of my lines on ftDNA but it is something I have been considering for some time now to see what I could learn more of in regard to the maternal side.

Recently, I posted about researching nine generations tied to the haplogroup L2a1 on my father’s side of the family. This line goes back to my 8th great-grandmother, Ana del Espíritu Santo.

Currently, I am trying to find a direct female descendant of Eglantine Lautin, my 5th great-grandmother in the hopes that mtDNA testing can teach us more about her origins in Africa.

Similarly, mtDNA testing is not super well known outside of the genealogical genetic testing world and usually one needs to find the descendants themselves and see if they are willing to test in order to help along with investigations.

Conclusions

Ultimately, I really enjoyed this exercise because it allowed me to take a different approach to the surnames in my family. Similarly, I did not realize how many “son of…” surnames I had recently in my tree; where 10/32 (almost 1/3) of the surnames in the generation of my 2nd great-grandparents is tied to these patronymic style surnames.

There are also surnames in my family tree that I have explored before, such as Chéverez and Lamboy/Laboy that are not super common outside of Puerto Rico and are curious surnames given their rarity outside of the island.

Ultimately, doing this activity also makes me want to test a few more lines for Y-DNA and/or mtDNA. Hmmm – one day!

References:

“Surname,” Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Surname : accessed 25 May 2024).

“Surnames – Jewish Names,” Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jewish_name#:~:text=Sephardic%20communities%20began%20to%20take,Spanish%2C%20Portuguese%2C%20and%20Italian : accessed 26 May 2024)

“Chinese Last Names: A History of Culture and Family,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/en/blog/chinese-last-names#:~:text=Origin%20of%20Chinese%20Last%20Names,poem%20Baijiaxing%20or%20Hundred%20Surnames : accessed 26 May 2024

“Spanish Naming Customs,” Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_naming_customs : accessed 25 May 2024)