When it comes to learning about our ancestors, we usually want to learn pretty much everything about them – no detail seems too small. How tall were they? What color eyes did they have? Where did they live and where did they work? And of course, who were their parents and where were they from?

But...

What happens when your family has skeletons in the closet? A murder or some other crime? Would you want to know? There are people that fall on both sides of the spectrum – the “DEFINITELY NOT” and the “SURE, OF COURSE” crowds.

Myself, I fall in the “sure, of course” crowd. Though it might not be seen as great information, it’s still information and in genealogy this can mean a lot! It gives me insight into the type of life or even family the person would have lived in. It makes me question what would have made them make that ultimate decision – or likely were they framed for a crime they did not commit?

Especially in Puerto Rico, finding any type of information that falls outside of the typical census, church, or civil registration records – I feel like there isn’t much. Of course, you can find the WWI and WWII records for men who were enlisted (though they might not have served), but even then those are for limited years as well.

Two years ago during the (first) pandemic summer, I started investigating prison records available online for Puerto Rico that I found via the blog “Genealogía Nuestra” – a great resource for Puerto Rico Genealogy!

Though the boxes (or cajas) are a bit all over the place in regards to years, I started to poke around to see what I could find. Similarly, the records are not indexed (either digitally or from what I saw in any list in their own boxes) so you have to blindly go in to search. Luckily, each set of records has a sort of cover page that includes the person’s name and sometimes a photo of the person in question.

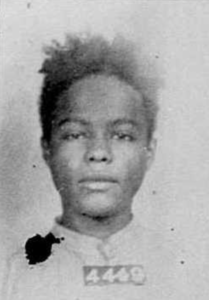

I was fortunate (unfortunate for the “definitely not” crowd) to find two records for family members, though they are not direct ancestors. In my case, I was lucky that these two files had photos which allowed me to take a glance into what my own ancestor might have looked like. In talking to my grandmother about one of the records, without even mentioning who the man was, she stated: “This man kind of looks like my grandfather” – the man was actually her great-grandfather’s brother so I guess looks run in the family! Having photos is also especially important for us Puerto Ricans when having mixed family member characteristics can run the gamut of what one branch looks like versus another.

With that said – let’s dive in!

Ramón chéverez ortiz

Source: “Cárceles 1800-1950,” expediente nº 4449, libro nº 26, folio nº 693, Ramón Chéverez Ortiz, proceedings, 21 March 1940; accessed as “Confinados fallecidos Caja 243-245, 1930-1943, Caja 1, 1800-1810, 1827,” browsable images, FamilySearch, (https://www.familysearch.org/search/catalog/612954 : accessed 21 March 2022). Search: Image 2262 of 6032.

As you can see from the photo above, Ramón (known in his record with the nickname “el negro monín”) looks rather young – and this is because he was! Around the time Ramón would have to appear in court for his case he was about 18-20 years old.

The cover page includes some identifying information about him, such as his parents’ names (José del Carmen Chéverez and Ramona Ortiz), he was a native of Corozal and also living there. According to the record he was 20 years old (since I don’t have his birth record I am not exactly sure what year he was born), and he was listed as jornalero (laborer). It gives some physical identifying information about him and lists his race as mulato. The record states he is in good health, Catholic, can read and write, and committed the crime in Toa Alta, but was living in the barrio (neighborhood) Dos Bocas in Corozal. Galateo is more in the heart of Toa Alta and is near Corozal but it boarders the barrio Quebrada Arenas – both barrios that I have family from in Toa Alta.

The record goes on to state that he was sentenced the 12th January 1939 to four years of forced work for “subsiguiente de huerto menor“. The four years would would end the 12th January 1943. On the back side of the document it states though that the 15th March 1940 and later the 21st March 1940 Ramón Chéverez Ortiz was released via “Habeas Corpus” – a law which protects against unlawful and indefinite imprisonment.

The Crime

The record goes on to state that before being sentenced for his crime in 1938, he had also committed two similar crimes the year prior in Río Piedras, Puerto Rico – one in April and was released in August and the second it seems he was sentenced the same day he was released (could his sentence just have been extended?) and later released a month later the 25th October 1937. Interestingly, this document states that he was condemned the 24th March 1938 and later released the 6th August 1938 (though it seems that he served longer given the ‘Habeas Corpus’ which also appears at the end of all of his documents.

The Toa Alta crime states that on the night of the 27th into the 28th December 1938 in the barrio Galateo, Toa Alta, he stole property from Francisco Lavadero. The property in question? A pig worth $25.00 at the time. The court record mentions given that he had been previously convicted and sentenced for similar crimes.

Now – you might just think, well it’s a simple pig! Couldn’t it just have been a simple prank or just a simple crime? True, but give that this happened between Christmas and New Year these are important celebrations and time of the year for Puerto Ricans (like Americans) when celebrating Christmas and the New Year – Puerto Ricans actually continue celebrating until the 6th of January for Three Kings’ Day. Usually a lechón (roasted pig) is made for the family and given that this happened in 1938, having pigs and meat to feed others I am sure was seen as something important – as we can see it was considered an offensive crime. My own grandmother still remembers not having much meat to eat and how valued it was in the house when they did have it.

The end of the record states that he was given Habeas Corpus and released 2-3 years earlier than expected.

Life After Prison

Though he does not appear in the 1940 census, he appears in the 1935 Census living with his mother in Dos Bocas, Corozal and a few other siblings. The next time I find Ramón on a record is on his death record in 1982 and unfortunately the death was a suicide of asphyxiation by hanging which states: “se privó de la vida ahorcándose“ (he deprived himself of life by hanging himself). He was around 61 years old.

I can imagine that serving time in his youth likely marked his life. Though, could this have been a cause for his ultimate death? He was married and had at least one child but besides that no more information is currently known about the life Ramón had after prison. He was fortunate to only serve a shorter time compared to the original four years but I can’t imagine serving time as a young man and what that would have been like between 1939-1940.

My surprise?

Really my surprise came from Ramón’s complexion (and not in a bad way). A lot of people on my dad’s side tend to be lighter or have more of a mixed look but with a sort of indigenous/European mix versus an African/European one. Ramón’s maternal grandfather, Manuel Ortiz Rivera, is my 3rd-great-granduncle. Manuel’s mother, Sotera Rivera Pacheco, was my 4th great-grandmother. Which means that between Ramón and I there are definitely a mix of ancestors given how far we are from one another in our trees. However, it is also possible that I am related to him via his father who was a Chéverez with origins in Toa Alta, like my own branch. And who knows if we are also related through the Marrero side that also likely goes back to Toa Alta. Given that many of his branches (and mine on my paternal grandfather’s side) were all mainly from Corozal and Toa Alta and my ancestors on this side were sometimes labeled as indio, I was greatly surprised when I saw his photo. Mainly because this makes me question what African genes I might have inherited from this side of the family – my family from the Toa Alta, Corozal area later would be labeled as pardos but I haven’t found any ancestors that have been enslaved going back to at least the 1700s.

Manuel Calderón Meléndez

Source: “Cárceles 1800-1950,” expediente nº 5632, libro nº 14, folio nº 981, Manuel Calderón Meléndez, proceedings, 16 June 1921; accessed as “Confinados fallecidos Caja 204-206, 1886, 1891, 1900, 1910-1920, 1897-1917, 1900-1922,” browsable images, FamilySearch, (https://www.familysearch.org/search/catalog/612954 : accessed 21 March 2022). Search: Image 2455 of 6320.

This was an interesting find for me – Manuel Calderón is my 3rd-great granduncle, his brother (Agustín) was my 3rd great-grandfather. What’s interesting is that this is a family which had changed surnames the next generation down and went by Meléndez, given that this generation (Manuel, Agustín, and his brothers were born out of wedlock). However, the prison record does state both of his parents (Juan Calderón and Crescencia Meléndez). He was a native of Vega Baja, a carpenter, married, 65 years old, and listed as blanco (white). On another page it lists his religion as espiritista (spiritualist) but does not list if he is able to read or write.

Manuel’s crime date is from the 3rd September 1919 and he was sentenced to two years and six months of forced labor which said would be until November 1921. However, it seems that Manuel completed his prison term in July 1921 (being released a few months earlier).

The Crime

Manuel’s crime is listed as a much more serious crime – Tentación de violación (attempt to rape). It seems the crime occurred the 27th August 1919 and he was quickly brought to court for it. Interestingly, Manuel’s prison records are fairly short – unlike Ramón’s it doesn’t go into detail on who brought forward this case and under what conditions it happened. I wonder if there was a minor involved and the court sought to protect this individual. Etched in ink on the back of a page it says: “cometió el delito en Vega Alta” (he committed the crime in Vega Alta). Who knows if there is more information in another box somewhere, but for now this is the only information I have on his case.

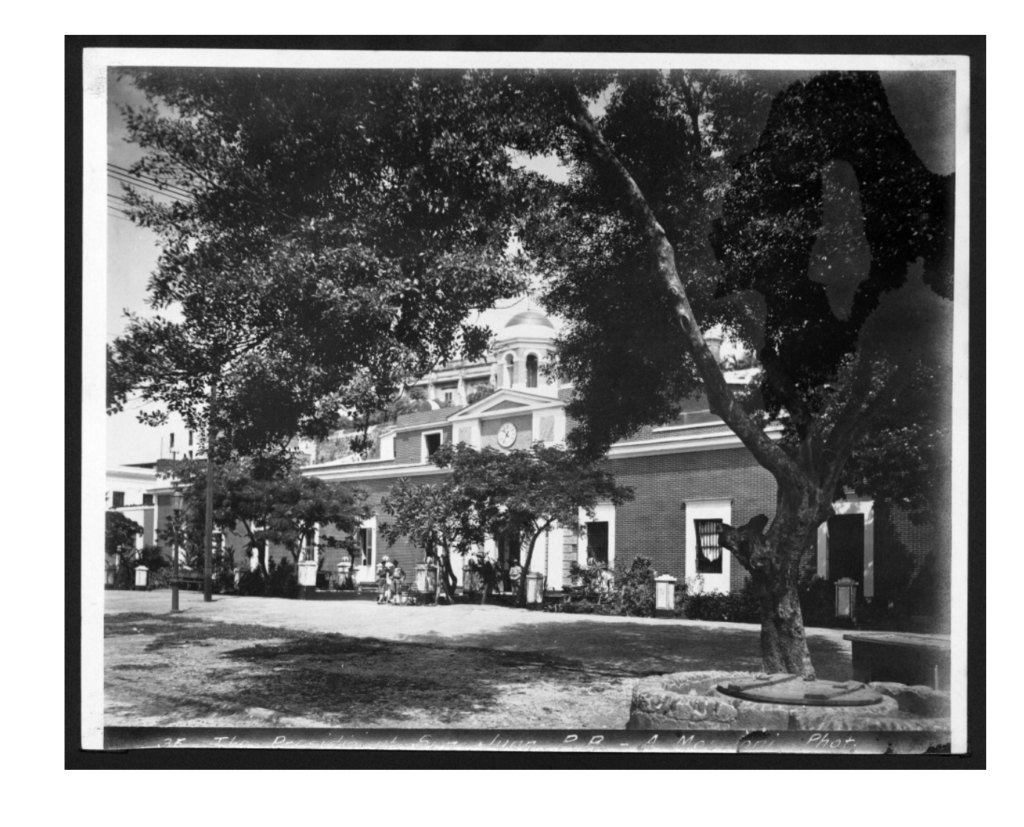

Manuel actually appears imprisoned on the 1920 Census in “La paseo de la princesa” in the San Juan Penitentiary in Barrio La Marina. If it’s the prison that I researched, it would be what is now the tourism office in Old San Juan (which I just walked by just this week!).

Source: “Antigua Cárcel La Princesa en el Viejo San Juan (entre 1898 y 1917),” GeoIsla (https://www.geoisla.com/2018/02/antigua-carcel-la-princesa-en-el-viejo-san-juan-entre-1898-y-1917/ : accessed 22 March 2022)

Life After Prison

Given Manuel’s age, he did not live long past his sentencing. Manuel would pass away the 18th March 1924 in Vega Alta, Puerto Rico. Though his death record states “80 years old” likely he was 70 years old based on other documents I have of him. His death record does not state his father’s name, only that he was an illegitimate son). Manuel had children before all of this happened and I wonder how his children would have felt as well as his wife. Manuel’s origins lie in Manatí and Vega Baja but it seems he never went back to his hometown which given what he went through would make sense.

I didn’t grow up knowing much of this side of my family so I’m not sure if there are stories out there about Manuel and what had happened.

My Surprise?

My surprise here came in two forms. The first was the listing of his father in his prison record. Though it’s not an official ‘genealogical’ record as how we see it in genealogy, having his name listed there while Manuel was in his 60s for me attests to the fact that my family should have been Calderón instead of Meléndez. I could have easily missed this record if I wasn’t attentive and could have skipped over it if I had not remembered that detail about this branch.

The second surprise was the photograph as well. This side of my family was lighter and Manuel was listed as white in his record. My great-grandfather was also fairly white but it seems a bit darker than Manuel, which makes me think what my great-grandmother’s family would have looked like. This side of my family is currently “brick-walled” given that a lot of these church records from towns like Vega Baja have not been digitized. So though I have names from the early 1800s, I can’t go back any further right now given the lack of documentation from that time period. There are cases to still solve from this family – for example, was there consanguinity amongst the Calderón?

Conclusion

There are still a ton of cajas to explore! I think I will have to create some sort of system so that I know which boxes I have seen and if there is some sort of rhyme or reason to them. Who knows how many other potential family members are buried in these files.

I know that I have some direct ancestors that appear in the Gazeta de Puerto Rico who were involved in different cases and I wonder if they would appear amongst these cajas. Though the cases occurred earlier which likely means there are no photos attached, it would still be interesting to read about what happened.

Hopefully in the future these will be digitized so that people can find and access the records much quicker!