If you grew up speaking Spanish or speak the language with elders, then you have likely heard the terms “Don” and “Doña” thrown around. Don Juan, Don Cheo (nickname for José), Doña Pancha (nickname for Francisca), or Doña María are some examples of this type of title being used. Generally, it is used nowadays to give a sort of elevated title of honor to that person. Whether inside or outside of the family, referring to someone as Don or Doña could be a way to address their age in a respectful manner. Usually, it is a title bestowed by the community onto the elder in question and rarely does the person name themselves this.

I remember the first time someone called my grandmother “Doña Carmen” and she slightly took offensive, “I’m not that old” she later said aloud. For some, it can be a way of seeming too old amongst other younger members of the community and they prefer to wait a few more years until they decide to finally accept the title.

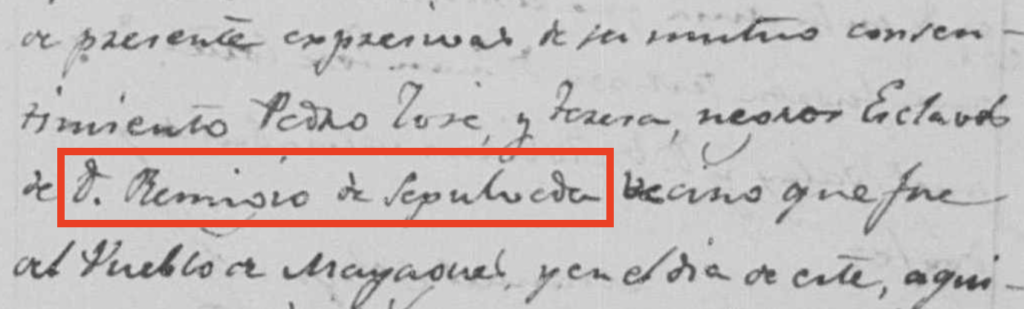

However, have you ever thought about the importance of the titles don or doña in genealogy? From the image above you can see that is a title recorded in vital records (I have only mostly seen them in death records) and can provide some clues to the life of the ancestor in question.

So in this post, I want to explore a bit this title and how it can provide some clues in your genealogical research.

The Title of Don/Doña

The first step as a good genealogist (and linguist!) is understanding the origin of the term don & doña. The first thing is the “a” at the end of doña marks the feminine gender, used in Spanish to refer to either people or objects. However, there are exceptions such as el papá (the father) which is masculine and la mano (the hand) which is feminine.

Following this general gender rule you will know that don will refer to a male ancestor while doña to a female ancestor.

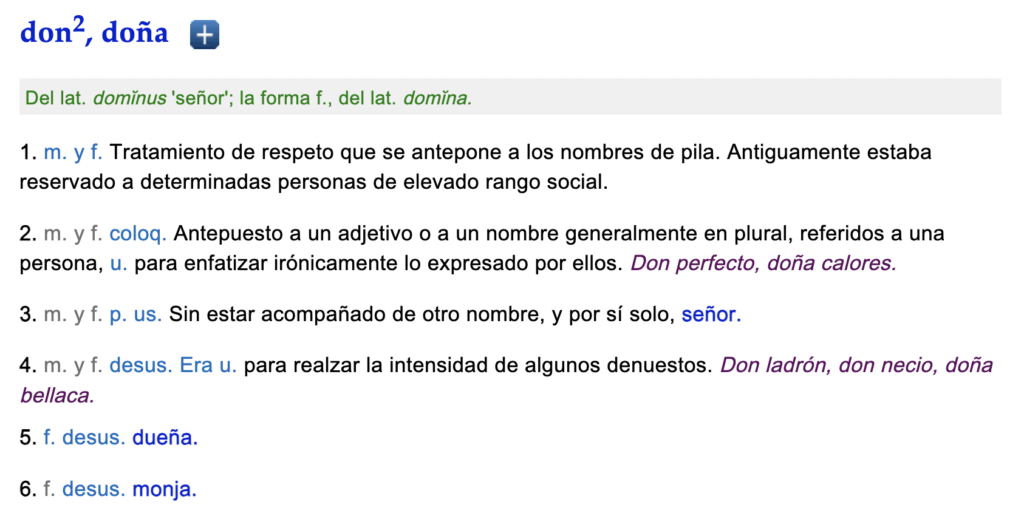

Taking a look at la Real Academia Española (RAE) we can see a few definitions for this word. It originates from latin’s dominus which means “sir” and its feminine form was domina. Definition #1 is the one that interests us the most and the closest to the definition I provided in the beginning. A quick translation of this definition is provided below:

“A treatment of respect which is placed in front of first names. Formerly reserved for determined people of elevated social rank”.

This would mean that though in the past it was likely used to refer almost exclusively to a person with social ranking (likely having some sort of status via land possession, money, etc.) nowadays you can still have the social respect without needing to provide proof of your social standing.

The second sentence is the most of interest to me and the one I will be exploring with emphasis on “elevated social rank”.

19th century usage

All the examples I found in my tree are from ancestors who passed away in the 19th century; ironically enough, all of them are ancestors who passed away in the town of Adjuntas as well. I do have other ancestors who were referred to as don or doña in other records but have not pinpointed those records as easily. When I find someone in my family that had carried one of the two I use the custom tags on Ancestry to mark the ancestor. But I should also mark specifically where/what documents had them written down as don or doña.

I want to focus on a few sets of ancestors in this post in regards to their status as don or doña, having picked three couples. This way I hope to provide a range of examples of when the term was used and what it potentially implicated. I chose a few set of ancestors that come from a specific cluster in my tree from the town of Adjuntas who show various levels of the social status of don and doña.

Don José María

Vélez Pérez

abt 1808-1865

José María Vélez was my 4th great-grandfather who was said to have been born in San Sebastián around 1808 and who died in Guayabo Dulce, Adjuntas, Puerto Rico on the 29th December 1865. José María Vélez Pérez, was the son of Gerónimo Vélez Rodríguez and María de los Reyes Pérez de la Cruz Sánchez (quite a name, I know!). I will talk about his parents as well a few entries down.

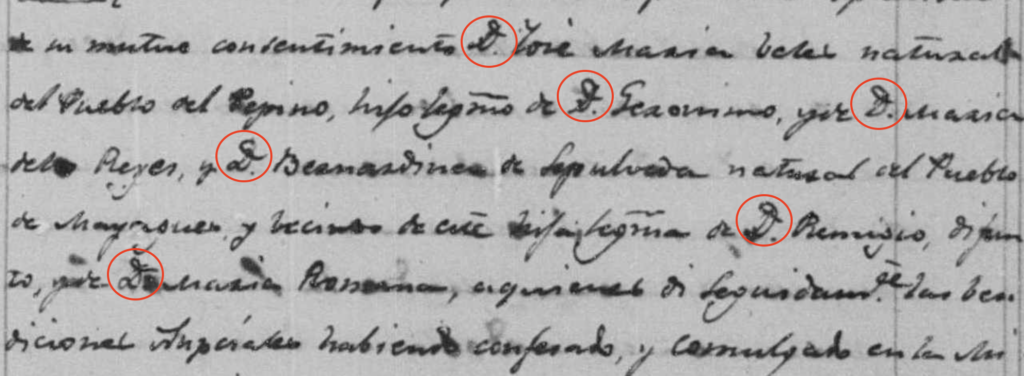

He married his wife Bernardina Sepúlveda Román in Adjuntas the 7th October 1829. When married, Jose María would have been around 21 years old and by then he already was using the title of don while his bride Bernardina, about 26 years old, was also referred to as doña. This helps to combat the notion that it was a title only for the elderly, if not, a social ranking that skirted around age. We can also see that all of their parents similarly held the same title, even Remigio Sepúlveda (Bernardina’s father) who was deceased was still referred to as don.

José María Vélez Pérez and Bernardina Sepúlveda Román were married in the first book of Adjuntas for white Puerto Ricans, which likely means that race also played an important role into who carried the title of don or doña. Most of my ancestors who carried this title were mostly referred to as blanco in the records. There are a few who were pardo (mixed race) and carried this title and even less (I am fairly sure none) who were classified as negro (black) who had this title. This is reflective of my family and though it does mirror society at the time, it does not mean there were not any wealthy and landowning pardos or negros in Puerto Rico.

At the time of José María Vélez Pérez’s death, though he was referred to as don and left a testamento (will) it seems it was not done in front of an actual notary. His will was listed in his death as “testamento mancomunado” translated into English as a “joint will”. According to the Diccionario panhispánico del español jurídico (Pan-hispanic Dictionary of Legal Spanish) this type of will was created between two or more parties that could be done for mutual benefit or the benefit of a third party. The person with whom José María Vélez Pérez created the will with were don José Antonio Rodríguez and two words after are illegible (potentially another person’s name – it looks something along the lines of Luis Cantalario/Candelario). Since neither was a notary it is likely that his will was not passed on to an archive, if it ever truly existed.

His death continues to list out his heirs, how he is to be buried, the masses to be prayed, and his executors. Interestingly enough, there is no mention of his wife as an heir or executor despite her being alive. Was it because Bernardina’s status was already cemented given her background and therefore was in no need of other worldly possessions?

Let’s explore some more!

Doña Bernardina Sepúlveda Román

abt 1803-1893

Bernardina Sepúlveda Román was born about 1808, the daughter of Remigio Sepúlveda Montalvo and María de la Cruz Román. She died the 10th March 1893 in Guayabo Dulce, Adjuntas, Puerto Rico. We know that by her mid-20s Bernardina was already being referred to as doña per her marriage record.

What is interesting though is that there are records to show that Bernardina was a slave owner – likely cementing her status in the mountainous elite of Puerto Rico. What we do not know via paper trail is what her husband’s role in slavery was. It seems that likely Bernardina inherited these slaves from her parents, who we will talk about in a bit.

The earliest mention of owning slaves we have so far is in 1866 when an enslaved woman named María died in Adjuntas, Puerto Rico. In her death, it mentioned that María was the daughter of Felipa and that she [María] was the slave of doña Bernardina Sepúlveda.

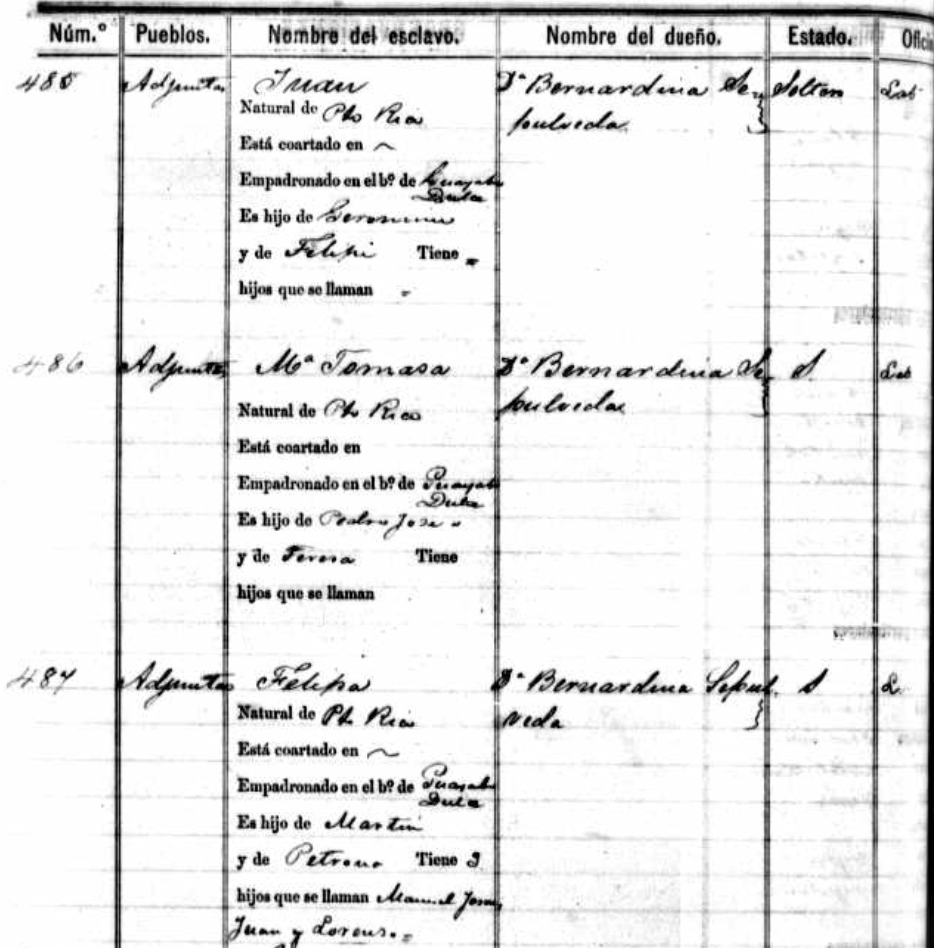

Later, in 1872 in the Registro Central de Esclavos (Central Slave Registry) we see that Bernardina was the owner of four enslaved people: (1) Lorenzo, (2) Juan, (3) María Tomasa, and (4) Felipa – the said mother of the deceased María.

Growing up I was never aware of this fact and had no idea or inkling that this family could have come from previous money or status. My grandmother and great-grandparents grew up fairly poor in Puerto Rico with my great-grandparents growing up in the rural mountainous towns of the island; but as you can see in their family’s past there was a history of owning slaves.

Shortly after this register, slavery would be abolished in Puerto Rico in 1873. Given that Bernardina had a small number of enslaved people, I am not sure in what capacity they would have worked – whether laboring at her home or on a field. Nonetheless, Bernardina would have to reconsider aspects of her life now that she could no longer own other humans.

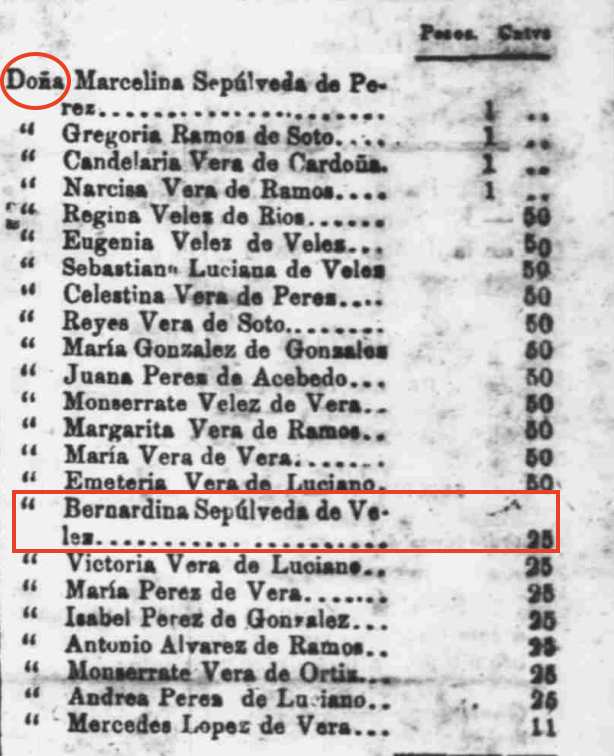

Three years later in 1876, Bernardina can be found listed in the Gazeta de Puerto Rico newspaper donating 25 centavos (cents – centavos was the Spanish currency) to aid others who had received any misfortune caused by hurricane San Felipe. We can see that Bernardina still retained the title of doña along with many other women who appeared to donate to this cause.

By the time Bernardina died in 1893, she is not listed as a doña on her death certificate and did not leave behind a will. Likely, given no slaves to transfer and possible loss of land (or previous transfers to children) Bernardina likely had nothing else left to her name.

What is interesting though is that her death states “no se confesó por no haberme solicitado ni testó” meaning “she did not confess because I was not requested and neither did she testify”. Bernardina would have been close to her early 90s when she passed so likely she did not die suddenly or unexpectedly. It is an interesting sentence that has left me interested in her death and its conditions.

Don Remigio

Sepúlveda Montalvo

1774-1829

Remigio Sepúlveda Montalvo was my 5th great-grandfather and the father of Bernardina Sepúlveda Román. Remigio was said to have been born the 11th January 1774 in Mayagüez, Puerto Rico to his parents Remigio Sepúlveda Vélez and Micaela Montalvo Dávila. Similarly, his marriage took place in Mayagüez to María de la Cruz Román Irizarry on the 21st February 1791.

Similarly to his daughter, Remigio was a slave owner and this is clear in the marriage of two of his slaves: Pedro José and Teresa. If you return to the image of the enslaved people Bernardina owned in 1872, you will notice that María Tomasa was the daughter of this couple. So you can see that Bernardina was transferred slaves from her parents.

When Remigio Sepúlveda died the 31st March 1829 he still carried the title of don. He left behind a testamento extrajudicial in front of five witnesses the 27th March 1829. He later mentioned his first executor of his will as his wife, his second executor a son-in-law named don Tomás Acevedo, and thirdly his own son don Juan Lorenzo Sepúlveda. Given that no notary is listed, we have no idea where/how to find his will given that is not tied to an actual notary – since it was extrajudicial I would imagine that it was done outside (extra-) the confines of the law (-judicial) and settled socially amongst them.

Doña María de la Cruz Román Irizarry

abt 1764-1854

María de la Cruz Román Irizarry was said to have been from San Sebastián, Puerto Rico and the daughter of José Román and Rosa Irizarry. She was my 5th great-grandmother and was married to Remigio Sepúlveda Montalvo.

She is to be one of the few ancestors that I was able to find a will based off of her death record. Listed as doña María Román in her death, she testified her will in December 1852 with the mayor of Adjuntas don Luis Chiesa (which I found to be fairly impressive and maybe even speaks to her social standing). In her actual will María de la Cruz Román lists out her property which included 450 acres of land in Adjuntas, 18 acres of land in Limón, Mayagüez, some farm animals, and lastly her slaves (13 in total).

You can read more about her will in my post (linked) where I posted before about how I found it at the Archivo General de Puerto Rico in San Juan based on her death record.

María de la Cruz Román Irizarry is probably a prime example of someone with the title of doña who carried a lot of power with it.

Don Gerónimo

Vélez Rodríguez

abt 1785-1855

Don Gerónimo Vélez Rodríguez was the father of José María Vélez Pérez, making Gerónimo my 5th great-grandfather. Gerónimo Vélez Rodríguez was said to have been from the town of San Sebastián and the son of Diego Vélez Rivera and Juana Rodríguez Irizarry (sometimes the second surname appears as Vargas).

Given that Gerónimo was not originally from Adjuntas and neither was his first born child, it is highly likely that he was married in another town (potentially San Sebastián itself). However, around the 1830s he and his wife were living in Adjuntas and continued to have children there.

When Gerónimo died the 11th March 1855 in Guayabo Dulce, Adjuntas, Puerto Rico he carried the title of don but then his death states “no testó por no tener de que según lo manifiestan sus deudos”. At first I thought this meant that he had some sort of debt given the word deudo but in fact the word is actually Spanish for “bereaved” or “mourners”. Which leads me to believe that when his family came forward to declare his death they also declared him without earthly posessions to leave behind. Gerónimo would have died somewhere in his 70s so it makes me wonder if it was an unexpected or expected death.

Doña María de los Reyes Pérez

abt 1793-1838

Lastly, I will focus on María de los Reyes Pérez de la Cruz Sánchez (my 5th great-grandmother) and wife of Gerónimo Vélez Rodríguez. She was also said to have been from San Sebastián and the daughter of Francisco Pérez de la Cruz and Ana Narcisa Sánchez. For the time being, I am unaware of either Gerónimo Vélez or María de los Reyes Pérez being slave owners but I am not ruling out the possibility.

María de los Reyes Pérez passed away before her husband in Adjuntas, Puerto Rico the 12th April 1838. She also left behind a will according to her death record but it was similar to Remigio Sepúlveda’s in which María appeared on the 9th March 1838 before four witnesses and left her will. Her death record listed out her children who are her heirs as well as her husband. Her executors were listed as first, her husband don Gerónimo Vélez, second her son don José María Vélez (my 4th great-grandfather talked about before), and finally her legitimate brother don José Valerio Pérez de la Cruz.

When wills are left in this manner I do wonder if this was shared wealth or land, money, and power that she would have inherited from her own parents and brought into the marriage.

Given that scarcity of these types of records in Puerto Rican genealogy, it is hard to piece together sometimes the social status many of our ancestors had. This is why paying attention to titles such as don and doña can be important to learning more about an ancestor’s social ranking.

Final Thoughts

This was a good exercise for me as it allowed me to better understand a few aspects of social ranking as well the function of some of these titles in death records. I was able to explore new terms such as testamento extrajudicial and testamento mancomunado as well.

Though the title of don or doña does not provide new names, dates, or towns of origins for ancestors it does give us some insight into social ranking and status they would have enjoyed during their lifetime. Whether it was inherited through their parents or acquired later in life, we can learn more about how our ancestors navigated the realm of status on the island of Puerto Rico. Just that in and of itself is important to better understand your family tree.

It would be interesting to further compare the intersectionality of race and gender when it comes to the use of these titles!

Cover Photo Source (Compiled images from the sources below):

Top left: Iglesia Católica San Joaquín (Adjuntas, Puerto Rico), “Libro 1 – Difuntos 1860-1868,” pg. 171, no. 714, José María Vélez, death, 29 December 1865; accessed as “Registros Parroquiales, 1854-1942,” browsable images, FamilySearch, (https://www.familysearch.org/search/catalog/412319 : accessed 20 July 2023).

Top Right: Iglesia Católica San Joaquín (Adjuntas, Puerto Rico), “Entierros [Burials] 24 agosto 1815-1859,” pg. 93v, no. 500, María de los Reyes Pérez, death, 12 April 1838; accessed as “Registros Parroquiales, 1854-1942,” browsable images, FamilySearch, (https://www.familysearch.org/search/catalog/412319 : accessed 20 July 2023).

Bottom Left: Iglesia Católica San Joaquín (Adjuntas, Puerto Rico), “Entierros [Burials] 24 agosto 1815-1859,” pg. 52v, no. 197, Remigio Sepúlveda, death, 31 March 1829; accessed as “Registros Parroquiales, 1854-1942,” browsable images, FamilySearch, (https://www.familysearch.org/search/catalog/412319 : accessed 20 July 2023).

Bottom Right: Iglesia Católica San Joaquín (Adjuntas, Puerto Rico), “Entierros [Burials] 24 agosto 1815-1859,” pg. 268v-269, no. 1382, María de la Cruz Román, death, 1 August 1854; accessed as “Registros Parroquiales, 1854-1942,” browsable images, FamilySearch, (https://www.familysearch.org/search/catalog/412319 : accessed 20 July 2023).

Thanks for a very good explanation of the use of the honorific title Don and Doña. I understand it was also used for militaty and naval officers as well

I have appreciated the same pattern. When you find the words “no testó”, It normally means the person did not leave any testament. It could also mean, that did not have any descendents. Did not necessarily mean that they did not have anything.

Why the priest did not write “doña” escapes my mind. Maybe because she did not confess before her death or he just did not write it there. An error of inscription of the many we find in the books.

Some people would leave their land or houses to their descendents or relatives before death. Fact that could not take away their “don” title.

I believe I have seen the use of the word “don” in the books of Loiza for the inscriptions of “Morenos Libres” or “Pardos Libres”. As a matter of fact, in Loiza and other towns “morenos”, “pardos” and “blancos” were written on the same Books. Some towns had separate books and others did not. In Loiza and Santurce, “Pardos” and “Morenos” had some sort of special standing since they were the majority of the population.

There were also “morenos libres” and “pardos Libres” which owned slaves. These slave owners, were normally merchants and farmers with no “don” title. In the books of Luquillo I found the defunction of a man with “Don” title that left no testament. ¿Did he have no money or land? ¿Why the “Don” title then?

I have observed that the Don title comes more often from family name, than from earthly possessions.

The notion of having a “Don” title for having money and possessions is a XX century notion.

The original “Don” title comes from nobility, military accomplishments and service in the administration to the monarch. Not for land and money. The Land and the money came after you earned that title. First you have to prove yourself in the military and the administration of the nation.

In the event of a death without land and money, that person was still a “don” or “doña”. That was something that nobody could take away from them. I’m my opinion Bernardina died being “Doña Bernardina”, regardless of the priest error in not writing it.