I was driven to do some investigative research on my 3rd great-grandfather and his siblings after a discussion on a Facebook post about the term “raza india” appearing as a racial category on Puerto Rican records. I had discovered my 3rd great-grandfather’s race labeled as “india” on his death record some time ago, but besides blogging about it once in the past, I never really paid much attention to it. So after seeing someone else question this racial category for their own ancestor, I decided to go back and do some more digging. My 3rd great-grandfather, Buenaventura Ortiz Rivera, was one of many children – could I find a pattern to their alleged race across various documents and siblings?

At the root of the tree - Ramón Ortiz & Sotera Rivera

It makes sense to begin with the parents of Buenaventura to hopefully provide us some more information and context. Based on Buenaventura’s death record in 1925 in Corozal, Puerto Rico – we know that his parents were named Ramón Ortiz and Sotera Rivera. Based on other records, it seems that Ramón died before 1885, meaning that we would have to turn to the Puerto Rican Church Records for more information. Sadly, there are currently no Corozal church records online which means that for the time being we are stuck with just the name “Ramón Ortiz” – who by the way has a very common name especially in the Corozal area.

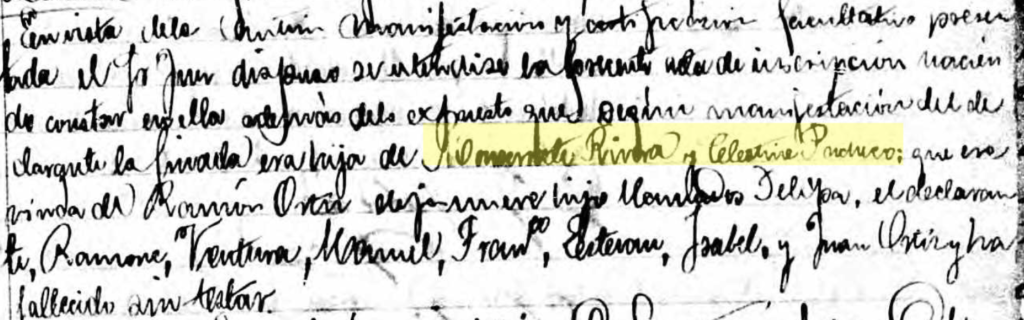

Sotera on the other hand passed away in 1897 in Corozal as well, specifically in barrio [neighborhood] Palos Blancos. She is listed as a widow of Ramón Ortiz with whom she had nine children: Felipa, Estanislao, Ramona, Ventura [Buenaventura], Manuel, Francisco, Esteban, Isabel, and Juan.

Her parents were listed as Monserrate Rivera and Celestina Pacheco, no racial category was listed for Sotera in her death record.

Given that Sotera was born in the early 1800s, I decided to check Toa Alta to see if I could find her baptism; this is because Corozal was not established as a town until the late 1700s- early 1800s and many people spilled over from Toa Alta to found Corozal. Though the entry I found mentions a “SoterO” (a boy instead of a girl), the couple registering the baptism is a Manuel Monserrate de Rivera and Celedonia Pacheco. It could be possible that the baby was either registered incorrectly or that this is a brother of my own Sotera. However, I am fairly sure this is the correct couple. Similarly, the name “Sotera” is not very common from what I have seen in my research.

You will also notice a discrepancy between Celestina and Celedonia but the names are very close and this is the only couple I found that fits name wise and time-frame wise. Also, death records are more likely to contain errors especially if the person declaring the death never met, for example, the parents of their mother or father.

Lastly, seeing as none of the Corozal baptism records are available online, we can not confirm via baptisms records for Buenaventura or his siblings the name of their grandparents… yet! Equally, no death records for Buenaventura’s siblings mention their grandparents.

Other children for Manuel Monserrate Rivera and Celedonia Pacheco have been found in Toa Alta, of course. For now, we will work with the fact that Celedonia Pacheco is likely the mother of Sotera Rivera Pacheco.

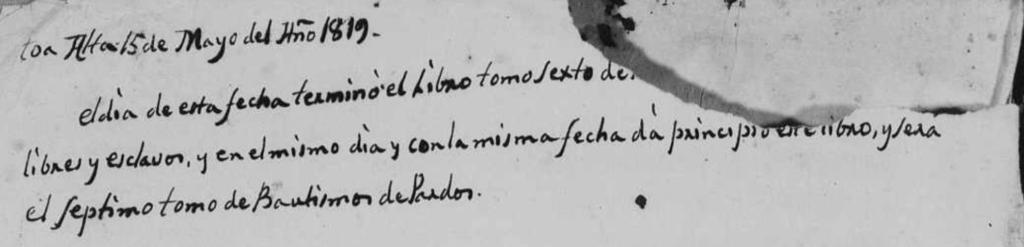

Though no race is listed in the actual entry for Sotera or any of the children being baptized on that page, usually in Toa Alta at the front of the baptismal book you can see what kind of baptisms were registered. Libro (Book) 7 which registered baptisms from 1819-1834 registered pardo children.

What is 'pardo'?

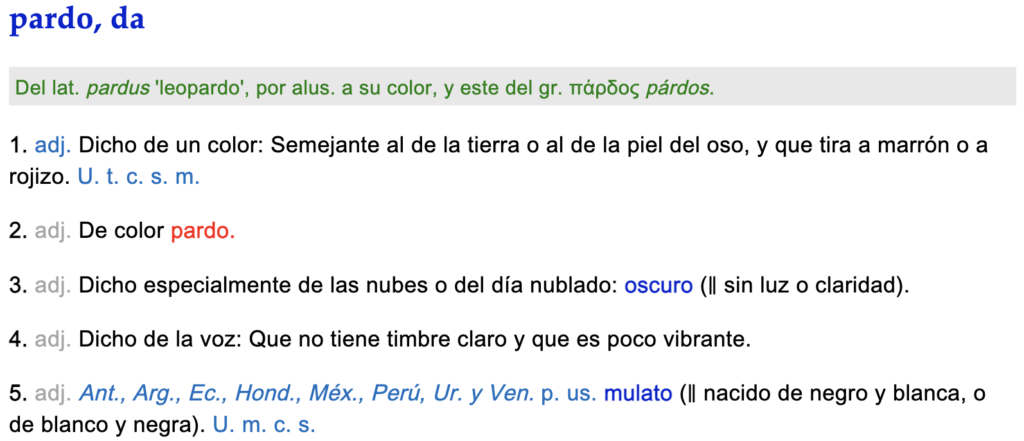

If you have done Puerto Rican genealogy using church records before, you have most likely come across this term. You can find it listed simply as “pardo” or even as “pardo libre“. But what does this term mean? There is a lot of debate about it actually! Looking at “La RAE” (Real Academia Española) for a modern take, we get various definitions listed below.

The most interesting definitions are #1 and #5, loosely translated as:

#1. adj. Said of a color: Close to the color of “earth” (dirt) or to [the color of] bear skin, and which leans towards brown or reddish.

#5. Ant., Arg. Ec., Hond., Méx., Perú, Ur. y Ven. p. us. mulatto (born from black and white, or from white and black).

Here in definition #5, the colors refer to the person’s racial (or phenotypical) category whereas the father is black and the mother is white or vice versa.

A quick Wikipedia search however tells us that it is the conglomeration of tri-racial descendants (Europeans, Amerindians, and West Africans), “defined as neither exclusively mestizo, nor mulatto, nor zambo”. (Wikipedia).

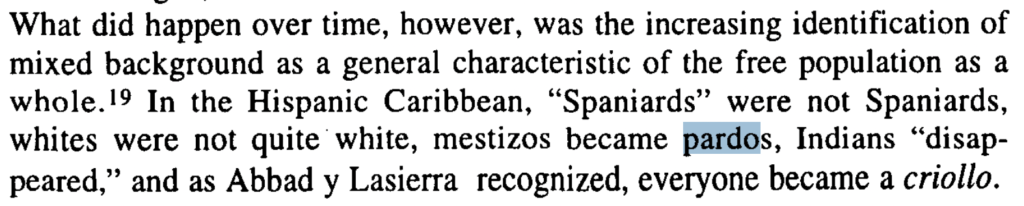

Stuart B. Schwartz sums it up best in his article titled “Spaniards, ‘pardos’, and the missing mestizos: identities and racial categories in the early Hispanic Caribbean“. See below for a snippet of his concluding thoughts.

So in conclusion, it seems we are talking about a group of people that to some degree was mixed and already moving towards an identity of criollo (creole). Considering that we are talking about a group of people that could have been on the island as early as the 1600s, this identity would have been almost 200 years in the making.

The "Ortiz Rivera" in Corozal

It seems that my 3rd great-grandfather and a good number of his siblings were likely all born in Corozal and lived there most (if not) all of their lives. From the nine siblings, it seems that only Isabel and Estanislao had left Corozal and died in Cataño and Naranjito, respectively. Likely the lives of my ancestors would have been similar to the images provided by the Library of Congress taken by Jack Delano – rolling hills of farm land they would have worked themselves throughout the 1800s-1900s. A distant cousin once mentioned that the family still owned land in barrio Palos Blancos (if I’m not mistaken) where our ancestors had lived.

In the 1910 census we learn that Buenaventura Ortiz Rivera worked as an agricultor (farmer) on a finca general (general farm) which he owned. In 1920 the farm was later classified as finca de café (coffee farm). Even in his death record in 1925, he was listed as 75 years old and still working as a farmer.

His brother Manuel Ortiz Rivera in 1910 was also working on a finca general he owned, as was another brother Francisco Ortiz Rivera – all in Palos Blancos.

Racial categories

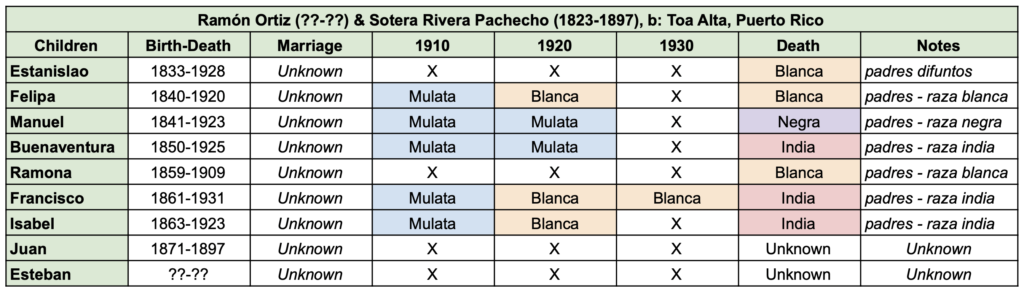

Compiling information from the 1910, 1920, and 1930 census (when available for each sibling) as well as death records, I was able to track racial categories for the Ortiz Rivera siblings. There are a few holes in the information such as baptism and marriage records because, again, we do not have any online for Corozal prior to 1885. Similarly, I have not been able to locate either Juan or Esteban’s death records.

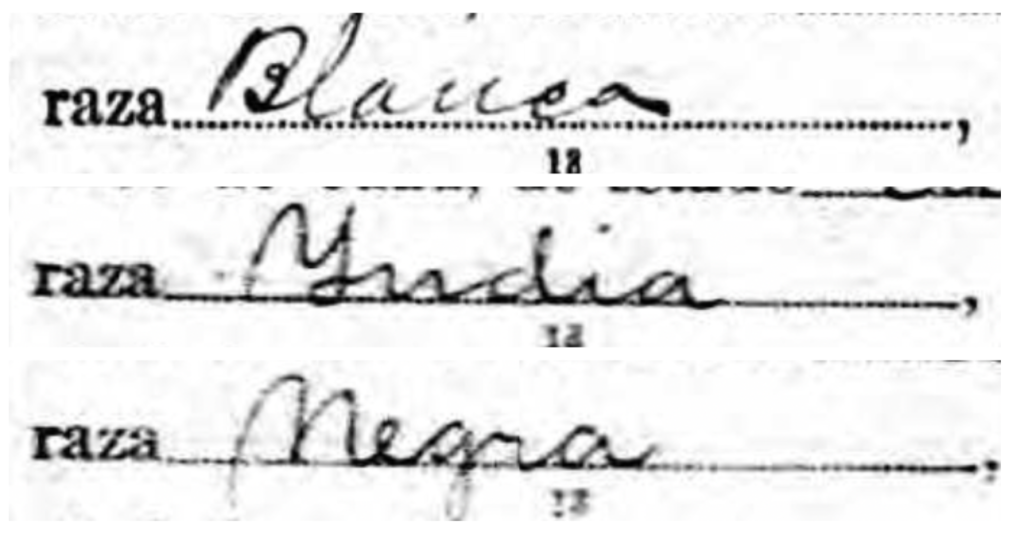

I tried to color coordinate the information a bit so that it would be easier to track. Out of the seven deaths recorded, three are listed as “raza india“, three as “raza blanca“, and one as “raza negra“.

What is interesting as well to notice is that Manuel and Buenaventura never appear as “raza blanca” on their census records while Felipa, Francisco, and Isabel did. Similarly, all of the siblings started as “raza mulata” in the 1910 census.

As you can see, the designation of race does not seem to be a “one size fits all” for the Ortiz Rivera siblings. Depending on who took the census, when they died, and who reported their death – could all be factors for what race would appear on each document. What is interesting to note is that even though Isabel left Corozal, she was still labeled as india in her death, while Estanislao was labeled as blanco in his death in Naranjito. Social mobility and wanting to be whiter in a culture that venerated (and still does) ‘whiteness’ might be part of the reason Estanislao, Felipa, and Ramona appear as raza blanca in their deaths. Since there are no photos of these family members it is not easy to know exactly where they fell in regards to “race”. We should also note that race is a social construct and thus who/how they identified varied on many factors both personally viewed and enforced by others.

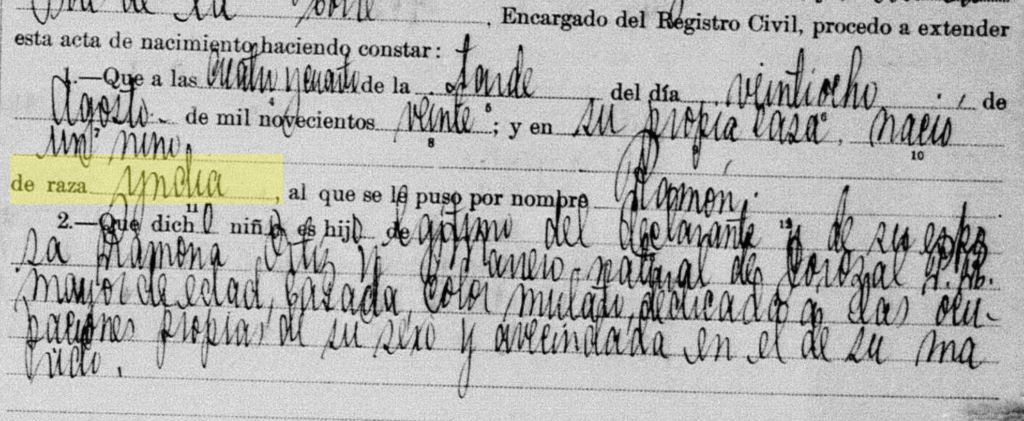

The only photo I do have is for a grandchild of Manuel Ortiz Rivera, via his daughter Ramona Ortiz Marrero. The child, Ramón Chéverez Ortiz, was actually a twin born the 28th August 1920 in Dos Bocas, Corozal, Puerto Rico. In his birth, Ramón was categorized as “raza india” and by his death (which sadly he took his own life in 1982) was recorded as raza blanca. However, taking a look at a photo provided from the time he spent in jail, you can see that in his youth he did not lean much to raza blanca. Another interesting tidbit is that his nickname was “el negro monín“. Around the time of the photo he was likely about 18 years old.

Source: “Cárceles 1800-1950,” expediente nº 4449, libro nº 26, folio nº 693, Ramón Chéverez Ortiz, proceedings, 21 March 1940; accessed as “Confinados fallecidos Caja 243-245, 1930-1943, Caja 1, 1800-1810, 1827,” browsable images, FamilySearch, (https://www.familysearch.org/search/catalog/612954 : accessed 21 March 2022). Search: Image 2262 of 6032.

A new feature on Ancestry allows you to colorize photos, which gives us a better glimpse at what Ramón Chéverez Ortiz actually would have looked like at the time it was taken.

DNA as

potential evidence

With the use of DNA Painter, I am able to personally compile and track whenever I get matches tied to certain ancestors, if and when I am able to pinpoint exactly where I match that genetic cousin based on my other family members’ DNA profiles. I have been fortunate to match one cousin back to Ramón Ortiz and Sotera Pacheco. This was done using my own family members’ DNA in comparison to this cousin and then comparing both of our genetic and paper trees to confirm we match exactly where we think we did. Since we are talking about my 4th great-grandparents here, the segments are fairly small and there is slightly more room for error (both potentially on paper and confirming where we match in DNA because we never know with things such as NPEs: Non-Paternity Events).

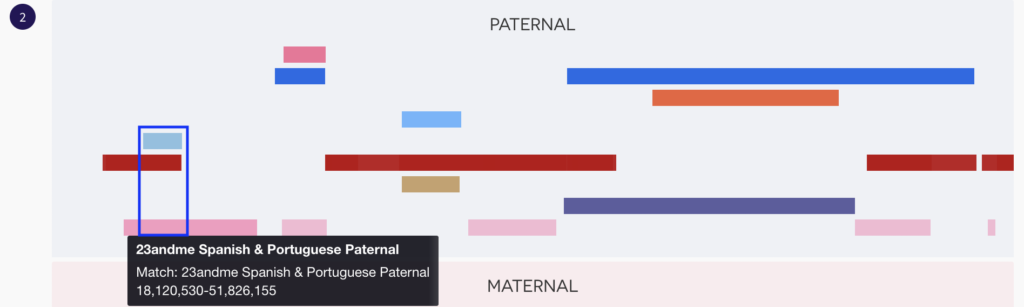

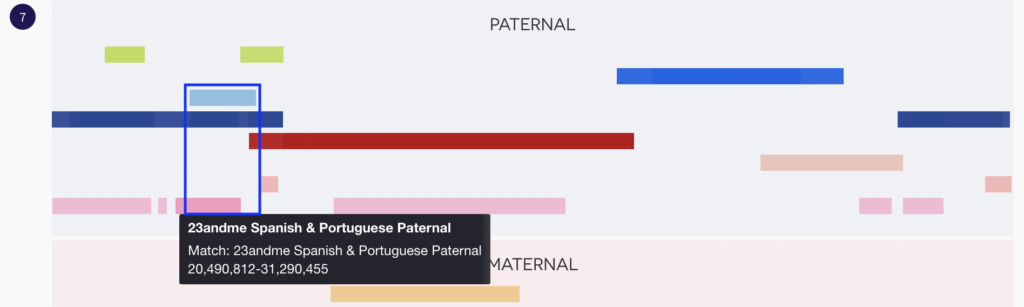

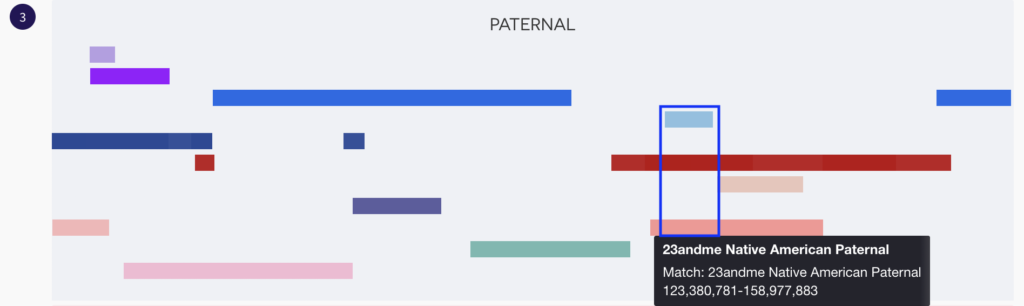

However, assuming what I have is correct, it is interesting to see where I overlap based on reference populations assigned to those specific segments. Below, you can see the light-ish blue segments inherited from Ramón Ortiz & Sotera Pacheco and where they overlap with a cultural reference point in my DNA pulled from 23andMe.

Below you can see that Chromosomes 2 and 7 overlap “Spanish & Portuguese” DNA while Chromosomes 3 and 5 overlap “Native American” DNA.

Now, this does not mean that Ramón Ortiz and Sotera Pacheco were only Spanish and Native mixed. There could have been other DNA segments such as West African DNA that I personally did not inherit given how recombination works and how far they are from me. Easily one of my brothers could have inherited other segments passed down from my dad that I personally did not pick up coupled with the fact that over the generations we lost segments along the way. However, it is interesting to see the native DNA there because it can help move the needle on the debate on the pardo identity with the fact that native DNA is likely present in many of those who were of this labeled category.

Final Thoughts

I do not personally believe that those who were labeled raza india in the 1800s were of pure Taíno or indigenous blood. For starters, the island had already been invaded for close to 400 years which would mean that the natives of the island would have had to constantly evade Spanish contact for that amount of time.

Could it have been possible? Possible… sure – I actually saw recently a 23andMe ancestry composition on Reddit of someone’s mother who was basically 100% native from out west in the mountains of Utah.

Is it possible for a Puerto Rican? I believe, likely no. Our highest mountains are not too high, meaning there really was not an area in Puerto Rico completely remote and isolated for 400 years without being discovered on such a small island.

As DNA becomes more useful and popular in Puerto Rican genealogy, I think it can be helpful for proving or verifying the category of pardo used back in the 1700-1800s. We know at some point there were pure indigenous ancestors in our lines, but what they might look like on paper is a complete mystery to me so far!

One last important note is that phenotype does not equal genotype. Many of our ancestors might have looked a certain way, and stories were passed down to us of ancestors who were pure “Taíno” or pure “Spanish” based on looks like long dark black hair or blue eyes. Yes, our ancestors did possess these phenotypic characteristics but a deeper look below the surface will show a mix of DNA.

One of my paternal great-grandmothers who I was told was the daughter of a Spanish man and a Taíno woman passed down an African maternal haplogroup while a maternal 2nd great-grandfather who had blue eyes and was told to be of Spanish stock has a mother who was registered as parda on her baptismal record.

So while my 3rd great-grandfather Buenaventura Ortiz Rivera was labeled raza india in his death record – I know that there is much more to the story than just those two words.