One of the biggest difficulties with Puerto Rican families when it comes to genealogy is the idea of consanguinity – when you share the same ancestors across a few of your branches. This is a common occurence on the island since many lines have been present in Puerto Rico for various generations and many date back to at least the early 1600s. What happens though when this becomes compounded generation after generation, literally one after the other? Likely in this case, we are dealing with endogamy – the custom of marrying within your own people (whether it be a tribe, family unit, religion, etc.).

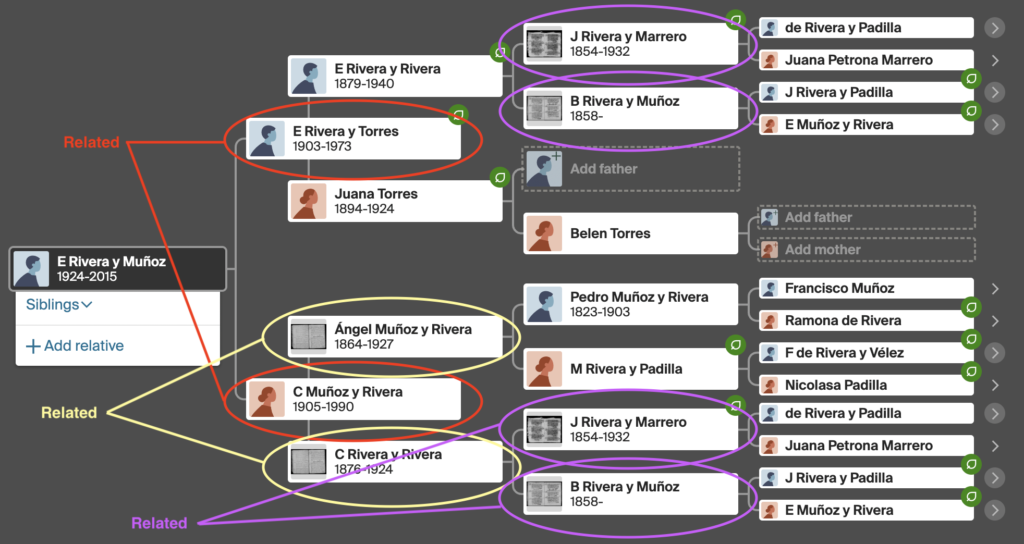

This seems to be the case of a family group within my family (not on my own main line but one that does cross my own ancestors’ descendants). As you can see from the picture above, the surname Rivera is sprinkled many times in that branch. However, currently I am not sure if they are related to my own Rivera line – both are from Toa Alta and it seems my family knew this family group given the years in question when they overlapped (early 1700s) and so I would not be surprised if somehow my own Rivera branch intermingled with this branch in the early years of Toa Alta’s history.

For now, I want to focus on these branches that seem to have purposefully intermarried three generations back to back and how this occurred.

Generation one

(Red)

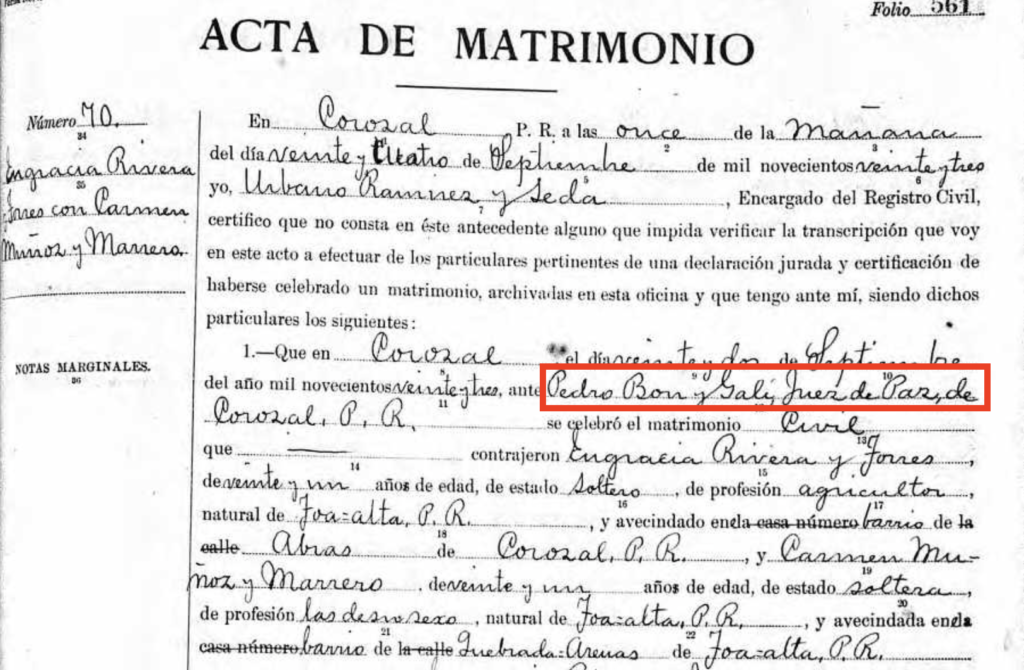

The first or rather the most recent generation to marry is a couple who married in 1923 – Engracia Rivera Torres and Carmen Muñoz Rivera, they married the 22nd September 1923 in Corozal, Puerto Rico. Since at this time marriages were occurring on a civil level via the Civil Registry of Puerto Rico and not always religiously (through the Parochial Registries), we can see that on their marriage it is noted that they were married by “Don Pedro Bou y Galí, Juez de Paz” [Justice of the Peace].

It’ is possible that since this marriage was civil, there was no need to check levels of consanguinity, however, there is something interesting to notice in the marriage record – Carmen is recorded as “Carmen Muñoz Marrero” and not as Carmen Muñoz Rivera. Her parents are listed as “Ángel Muñoz Maldonado” and “Carmen Marrero”. Other records though show that Carmen was the daughter of “Ángel Muñoz Rivera” and “Carmen Rivera Marrero”, I wonder if this was a deliberate “slip up”, seeing as how if going by what other documents show Engracia and Carmen would have been first cousins, both of their parents were “Rivera Rivera”, children of the same couple.

A couple of other pieces of evidence point to Carmen being a “Muñoz Rivera” and NOT a “Muñoz Marrero”.

For example,

1) in 1910 she is listed as Carmen Muñoz Rivera living with her widowed father, Ángel Muñoz Rivera. [1]

2) Her birth record in 1905 lists her as “María del Carmen Muñoz Rivera”, daughter of Ángel Muñoz Rivera & Carmen Rivera Rivera. [2]

3) Her death record in 1990 also records her as “Carmen Muñoz Rivera”, wife of Engracia Rivera, daughter of Ángel Muñoz & Carmen Rivera. [3]

This leads me to believe that with a quick sleight of hand, the couple was able to get married and avoid suspicious eyes when it came to consanguinity.

Generation Two (Yellow)

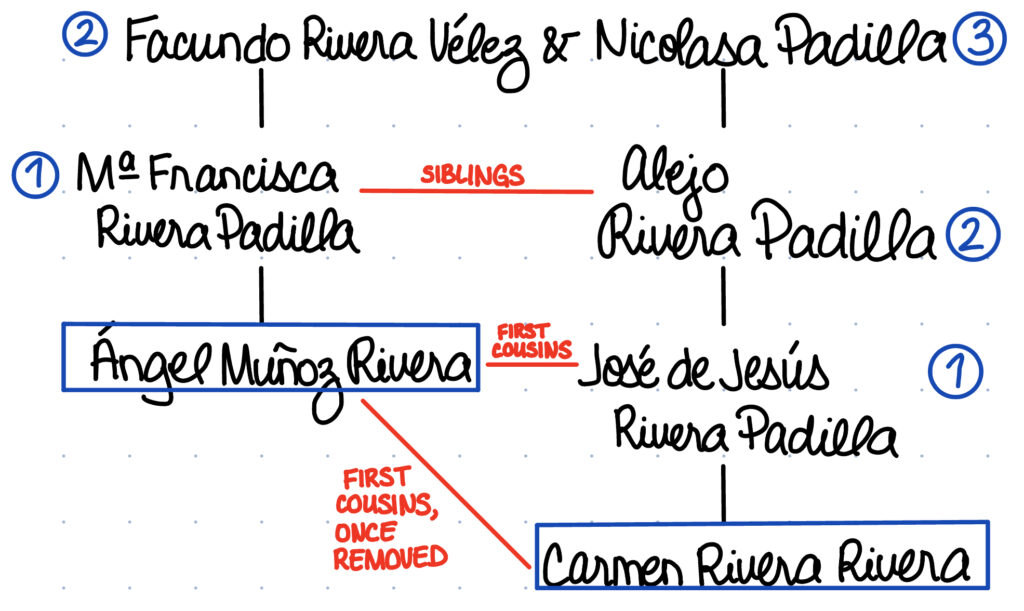

From the previous generation we see that Engracia Rivera Torres’ father (Emeterio Rivera Rivera) and Carmen Muñoz Rivera’s mother (Carmen Rivera Rivera) were siblings, both children of José de Jesús Rivera Marrero and Benigna Rivera Muñoz. (The names are cut out in the original image above given the length of the names). However, just looking at Carmen’s side we can see that her own parents were related as well.

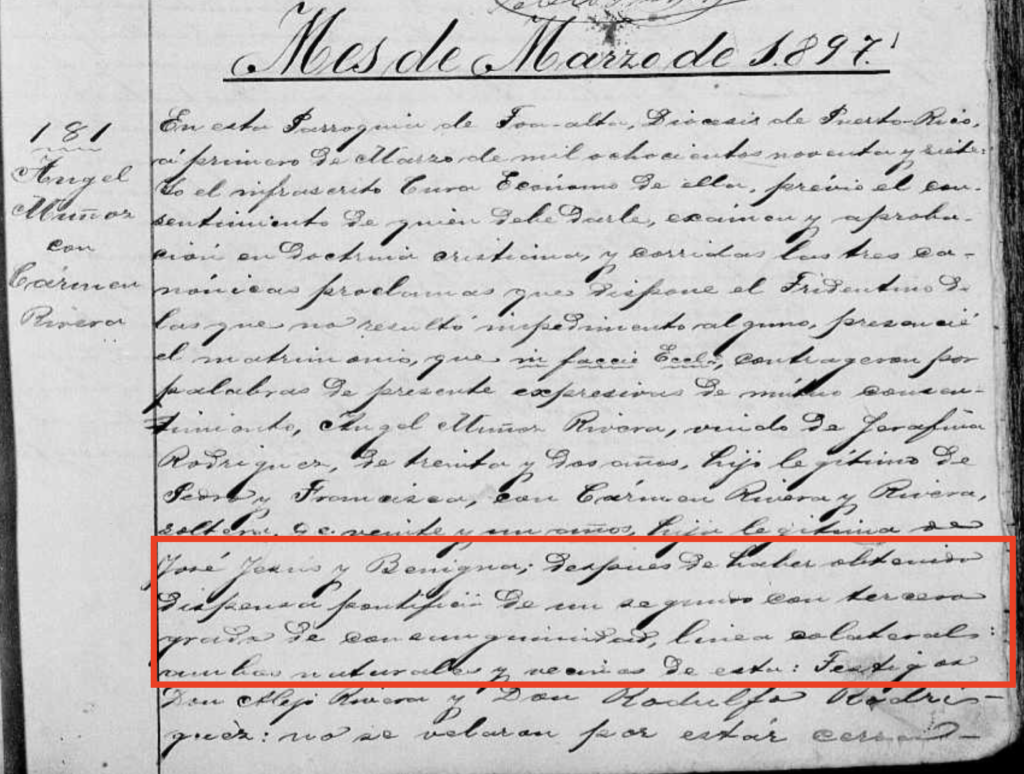

Ángel Muñoz Rivera and Carmen Rivera Rivera appeared in Toa Alta on the 11 March 1897 to get married. Their marriage was recorded twice – once on a civil level, and once on a religious level – they did register their level of consanguinity on their religious marriage. This puts into question if the Civil Registry checked at all. Both civil and marriage entries were recorded in the same time frame and social period, so it seems that consanguinity was more of a religious taboo than a social one.

When looking at Puerto Rican marriage records it is important to see if a religious equivalent exists where a parentesco (relationship) might be declared. If no known relationship was declared, this meant that the couple was not related (at least to a degree that would bother the church).

Their marriage states: “…de haber obtenido dispensa pontificia de un segundo grado con tercer grado de consanguinidad, línea colateral: ambos naturales y vecinos de ésta…” (having obtained a pontifical dispensation of a second with third degree of consanguinity, collateral line: both natural and neighbors of this [town]).

A second with third degree of consanguinity means that you would have to go back two and three generations to find the relationship between the couple. Luckily, since many of the church records for Toa Alta are available, it was not too difficult finding their relationships. Equally, in San Juan there is an Archivo Diocesano where likely their marriage dispensation might be located. However, though many were registered, not all of them made it to the central office and or saved, therefore using genealogical records to trace back the relationship is just as important when completing your research.

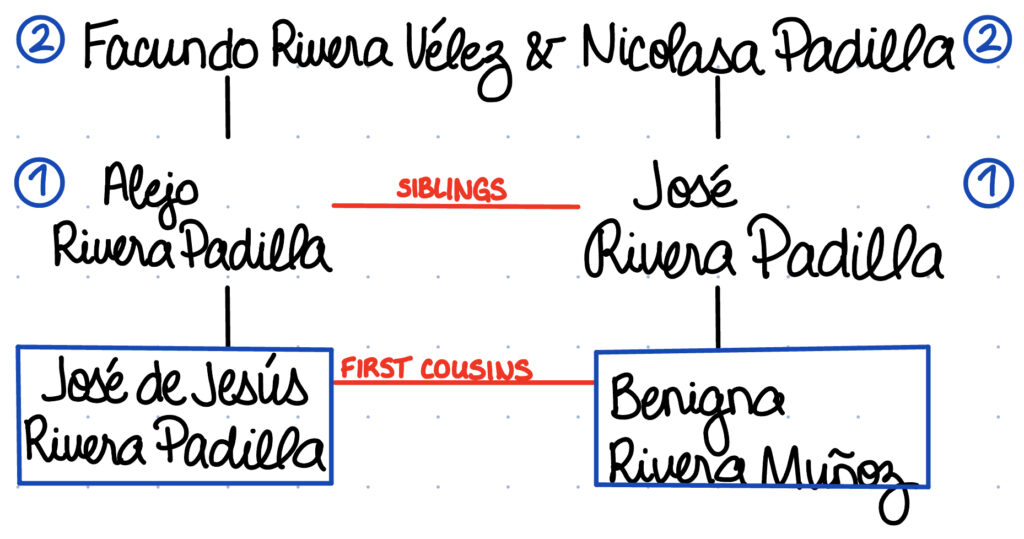

Below is a drawn relationship chart showing how Ángel Muñoz Rivera and his wife Carmen Rivera Rivera were related.

Building trees up towards a common couple can be super useful for determining relationship degrees and for seeing how your tree may be intertwined. For my family, in the 1900s-1800s there is not much intermingling between the lines. However, the further you go back and the smaller towns and population sizes become, the more likely I am to bump into lines that married each other. So far I have one case on my father’s side of the family between a set of my 3rd great-grandparents back in 1863 but I can not think of many other shared ancestors in my tree.

Generation Three (Purple)

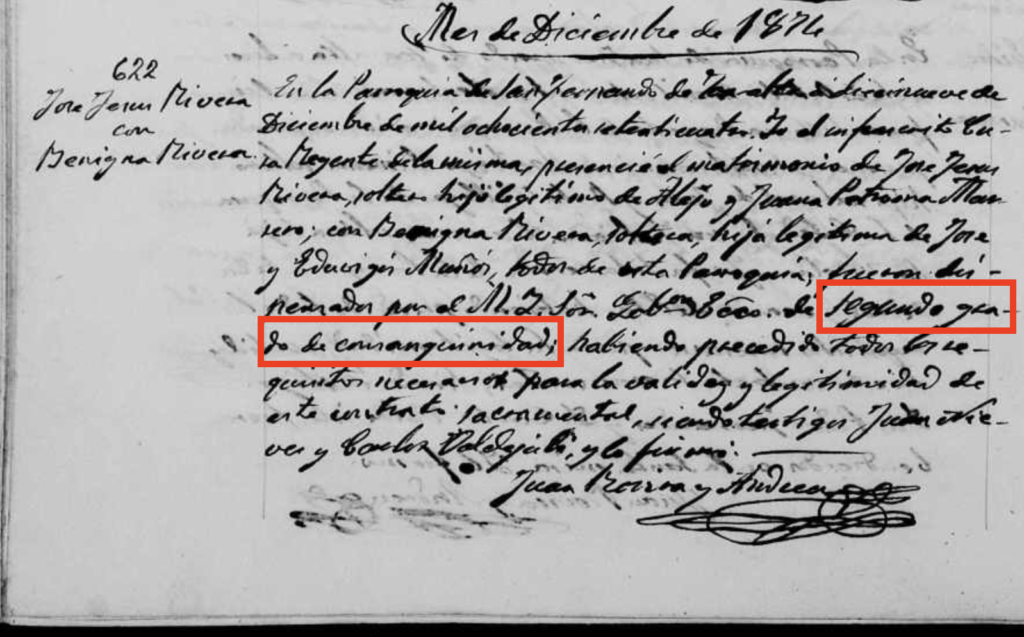

Lastly, the known generation to show a level of consanguinity is José de Jesús Rivera Marrero and Benigna Rivera Muñoz. When they married on the 19th December 1874 in Toa Alta, their marriage was registered with a 2º grade of consanguinity.

A 2º grade of consanguinity would mean that going up from the married couple would have the same ‘steps’ – two generations up. Drawing out another chart of this relationship will help us see which lines they share.

As you can see above, the couple at the root is Facundo Rivera Vélez & Nicolasa Padilla. We have seen this couple before since María Francisca Rivera Padilla is also a child of this couple. So we can see that the Rivera Padilla clan was fairly endogamous.

Given the limited range of years for the church records in Toa Alta, we do not know how many more times this family unit might have married in the past. Whether or not this only occurred in the 19th century or already comes from further generations in this town, we might not know for certain.

Consanguineous implications

When it comes to analyzing your family tree and the DNA you have inherited, these type of relationships may alter the way other cousins may show up on your tree. This is an issue for a few cultural and religious groups and Puerto Ricans are amongst them. Many times I have received a match that seemed close but when you looked at the inherited DNA, they were sliced up into very small segments (meaning they likely were not inherited from a close ancestor) and when looking at similar surnames and town origins, there was not an overlap in the estimated range provided by DNA companies. Of course, there is also the likelihood of Non-Paternity Events which is a whole other can of worms.

For the most part, it seems that many Puerto Ricans who have been on the island for many centuries will come across this issue at some point (whether on paper on in DNA); this is then compounded when families decide (for whatever reason) to continue purposefully marry amongst themselves as well. It is probably one of the biggest issues ‘plaguing’ the Puerto Rican community when it comes to DNA matches and diversity amongst matches as well.

Hopefully in the future, endogamous and consanguineous populations will be able to use DNA to the same level as other less mixed together groups are able to do. Until then, we have to be very cautious of these type of relationships amongst our branches!

Sources:

[1] 1910 U.S. Federal Census, Corozal, Puerto Rico, population schedule, Barrio Río Lajas, Enumeration District (ED) 101, sheet 12-B, p. 1926 (inked), dwelling 97, family 98, Ángel Muñoz Rivera household; Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/7884/ : accessed 27 May 2023); citing NARA microfilm publication T624, roll 1780.

[2] Registro Civil (Corozal, Puerto Rico), “Nacimientos 1892-1907, L. 8-12,” no. 151, Carmen Muñoz Rivera, birth, 1 October 1905; accessed as “Puerto Rico, Civil Registry, 1805-2001,” browsable images, FamilySearch, (https://www.familysearch.org/search/collection/1682798 : accessed 27 May 2023). Image 1949 out of 2219.

[3] Registro Civil (Bayamón, Puerto Rico), “Defunciones, mar. 1990-oct. 1991,” no. 717 Carmen Muñoz Rivera, death, 17 July 1990; accessed as “Puerto Rico, Civil Registry, 1885-2001,” browsable images, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/9100/: accessed 27 May 2023).

My paternal grandparents were half first parents once removed and also fourth cousins. I also had fifth great-grandparents that were third cousins.

That should be cousins instead of parents after first in the sentence.