Last July, 23andMe blogged about a recently (at the time) published article that looked at genetics and the legacy the transatlantic slave trade left on the New World (specifically countries like the United States, countries in the Caribbean and in Latin America which were main receivers of enslaved people). Their post (23andMe blog linked) offers a succinct look at the paper/study which they published. Being the genealogist I am, I wanted to read the actual paper and see how it related directly to me and I thought it would be worth seeing the academic side of their blog, especially if this was something I want to consider doing myself in the future – writing academic papers tied to genealogy and genetics. My goal was to include this post as my last February post and in honor of my African ancestors, but unfortunately the end of the month turned out a bit busier than I expected, despite having already read the article, but I still want to blog about what I had learned.

The genetic article published can be accessed HERE and read for free. There are two versions available, I read the shorter version which was 13 pages.

Genetic Consequences of the transatlantic slave trade in the americas

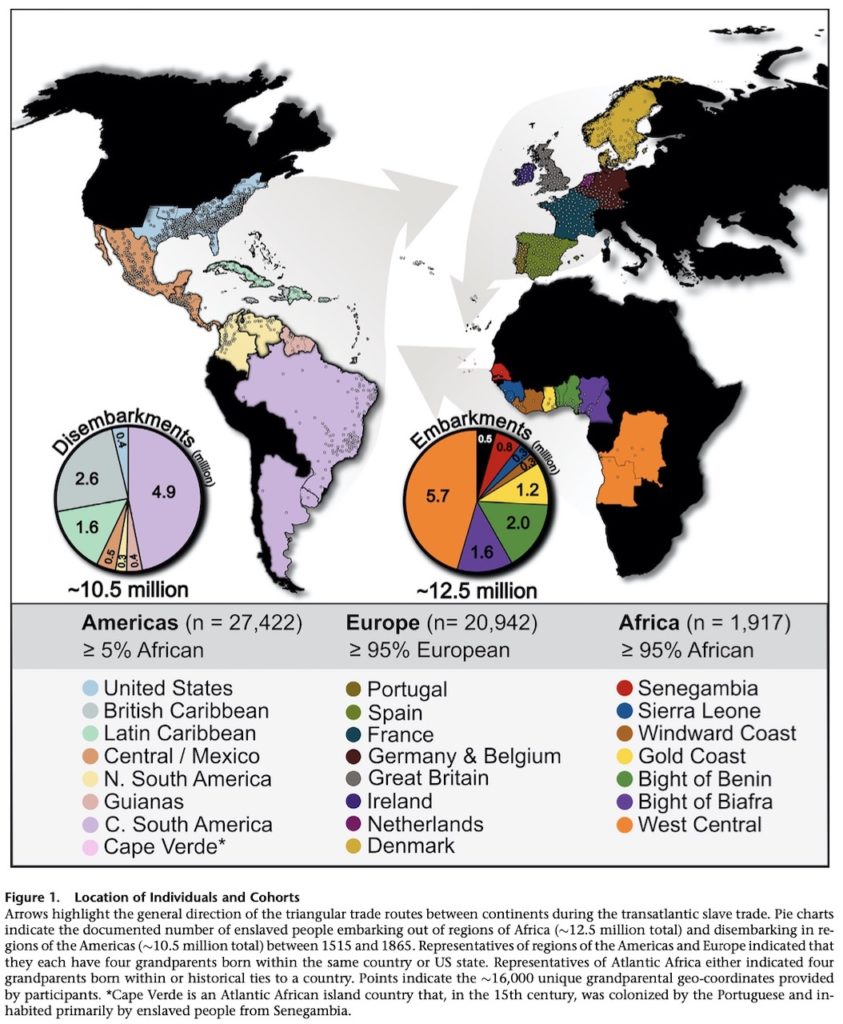

Overall, the article was extremely interesting, both in regards to information and statistics compiled and genetic information offered in their study, specifically of interest to me for the enslaved people brought to the Caribbean. To begin with it is an interesting (and at this point I’m not sure how well known it is) fact that more African slaves were brought into the New World through the Caribbean and Brasil versus into North America.

“For example, shipping manifests indicate that the number of enslaved people disembarking at Brazilian and Caribbean ports was far greater than the number disembarking at other ports in the Americas. An estimated 10.1 million enslaved people, primarily male, disembarked in Central America, South America, and the Caribbean (accounting for more than 90% of all captives who were brought to the Americas), with fewer than half a million disembarking in mainland America (3% to 5% of the total)” (The American Journal of Human Genetics, 107, 265-277, August 6, 2020, p. 265). [Emphasis my own.]

An interesting point the article makes is: “despite a majority of enslaved Africans disembarking into Latin America, estimates of proportion of African ancestry for Latin Americans with African roots are lower on average than estimates for African Americans in the United States” (The American Journal of Human Genetics, 107, 265-277, August 6, 2020, p. 265).

In my family for example, there is a range of African scores per 23andMe and AncestryDNA but none overpower the European DNA we have received. My grandfather has the highest African DNA amongst my family members and research has shown this is likely due to his recent connection to enslavement via Martinique and Guadeloupe. You can read more about the African breakdown in my family in this post titled “A Puerto Rican Look at: Generational 23andMe African Ancestry“. In my other post titled: “A Puerto Rican Look at: A Generational Exploration of African Ancestry” looks into my African DNA via AncestryDNA and compare it to information provided by FonteFelipe’s Tracing African Roots blog about African DNA in the diaspora.

Another important point in the article’s first pages is that: “Prior to 1650, slave voyages most often originated in Senegambia and West Central Africa (in locations now known as the Democratic Republic of Congo and Angola) […] the slave trading period (from 1650 to 1850), […] increasing frequency at ports in the Bight of Benin and the Bight of Biafra, in locations now known as Benin, Nigeria, Cameroon, and Gabon” (The American Journal of Human Genetics, 107, 265-277, August 6, 2020, p. 265).

I found this important to mention because 1) Puerto Ricans tend to show a higher Senegambia DNA import from enslaved ancestors, likely from these beginning slave trades, and 2) it’s important to see where slave voyages started and then were shifts occurred along the coast causing other countries to become involved, such as Nigeria where my grandfather’s DNA has a higher concentration – likely a product of enslaved people brought to the French islands in the mid/late 1700s (Guadeloupe) and early 1800s (Martinique).

The image below provides an idea into the disembarkments and embarkments by showing in the millions how many left Africa into the New World and the route of what is known as the “Triangular Trade”.

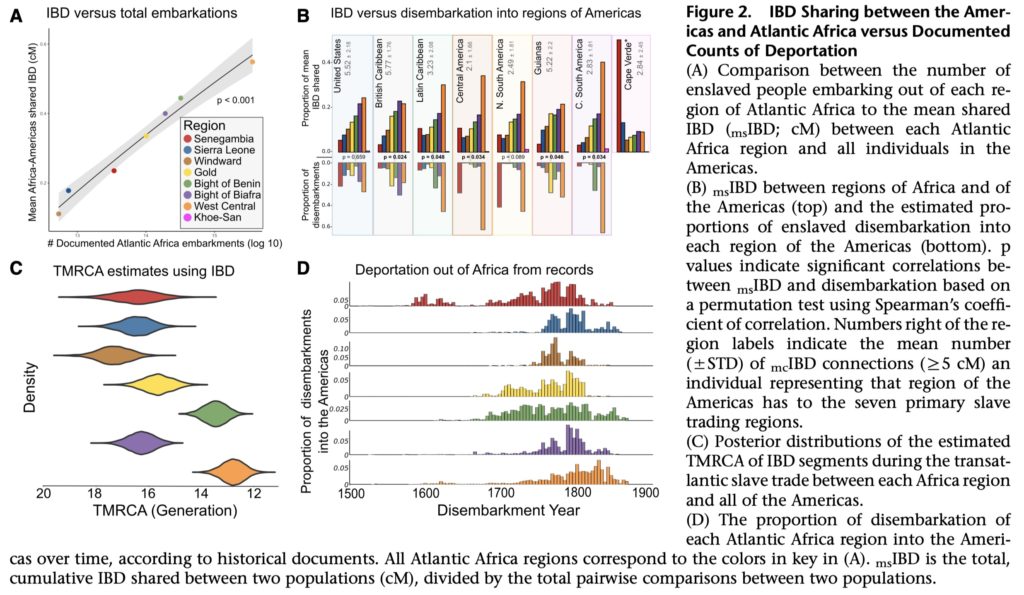

The article beings to talk about the methodology of its study as well as the science used to identify “Identity by Descent” (IBD) segments and the use of local populations by 23andMe to identify areas in Africa tied back to enslaved people in the New World. One interesting fact that stuck out to me was: “Assuming a generation time of 20 to 27 years, the transatlantic slave trade began roughly 14 to 20 generations ago” (The American Journal of Human Genetics, 107, 265-277, August 6, 2020, p. 269). [Emphasis my own.]

For many of us genealogists, especially working to identify our indigenous and African roots, 14-20 generations can be an extremely difficult place to reach via paper trail. This is why DNA testing is important in our search for our roots. If you took the lowest number of a generation (20 years) and multiplied that by 14 you get 280 years, minus our current year of 2021 you get back to the year 1741. For some people, they might be lucky in identifying an enslaved ancestor from that time period but potentially never identifying their origin. In a previous post I had discussed “Manuel Ruiz, a pardo slave in the 1700s” who lived in Coamo, but two problems arose here: 1) He was a pardo slave so likely he was already mixed and was not directly brought over from Africa, 2) No records mention parents which means this is currently where the line ends for me. For many BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) these are the issues we come across when researching and why studies like this done by 23andMe can be important in shining a light into this dark past.

A couple of important points were discussed to the end of the article. Here are some interesting take aways I noticed.

“Ancestry inference in the Americas reveals that the majority of the individuals within the United States (93%) as well as from the British and French Caribbean (82%) tend to have ancestry from all four of these Atlantic African populations, with Nigeria being the most common of the four. A high proportion of individuals from the Guianas (64%) and the Latin Caribbean (44%) also have ancestry from all four populations, with Costal West African ancestry in the Guianas being most common relative to the other Atlantic African ancestries, and Senegambian being most common in the Latin Caribbean” (The American Journal of Human Genetics, 107, 265-277, August 6, 2020, p. 270). [Emphasis my own.]

This did not strike me as surprising given all of the information I have already seen and as I had mentioned FonteFelipe’s blog Tracing African Roots does a great job at making some of these connections as well. I was however happily surprised to see the higher Nigerian DNA in the French Caribbean since this is something I had noticed as well within my own family. In my blog post “Genetic Connections to Guadeloupe” I explore some African DNA overlap connections I share with people from Guadeloupe who are likely tied to my 4th great-grandfather Gustave Jean Charles, born in Terre-de-Bas, Guadeloupe – the son of Chaleau Jean Charles and Marie Lucie.

One of the more important points were biases in the gene pool based on male and female contribution. For example: “We identified a bias toward European male and African female genetic contributions across regions of the Americas using the sex-specific model for admixture, which assumes admixture events during the transatlantic slave trade” (The American Journal of Human Genetics, 107, 265-277, August 6, 2020, p. 270). The article later mentions that this “sex-bias discordance” can be accounted for on various levels such as rape of enslaved African women by slave owners, branqueamento (racial whitening), and even incentivizing enslaved women to produce children with a promise of freedom (The American Journal of Human Genetics, 107, 265-277, August 6, 2020, p. 273). For anyone who has studied enslavement, these come to us as no surprise of what humanity was capable of in order to get away with social and racial stratification.

To put the discordance into numbers, the article states: “However, this African female sex bias is more extreme in Latin America (between 4 and 17 African women for every African man contributing to the gene pool) than in British-colonized Americas (between 1.5 and 2 African women for every African man contributing to the gene pool” (The American Journal of Human Genetics, 107, 265-277, August 6, 2020, p. 273).

Another point I found interesting was: “These voyages would spread African ancestry common in the British Caribbean to other regions of the Americas that were not in direct trade with specific regions of Africa. In Latin America, transatlantic slave trading voyages virtually ceased between 1660 and 1780, yet a large proportion of all documented captives continued to be transported throughout the early 1800s to Latin America primarily from the British Caribbean” (The American Journal of Human Genetics, 107, 265-277, August 6, 2020, p. 272).

This is an important fact to keep in mind when you match people who share DNA with you but not a similar cultural background. I experienced this and wrote about it on my blog post titled “Chromosome 7 – An African American Connection” in which I connect with various men from the United States (most with connections to the US South) who are primarily of African American descent and share with me a piece of Congolese DNA.

Conclusions

Finally, the article talks a bit into the future of identifying African DNA and some of the limitations they came across while writing this article. One point they make is underrepresentation: “The underrepresentation of ancestral connections to Senegambia also occurs in regions of the Americas with more recent (1700-1865) disembarkation from Senegambia, such as the United States and Latin Caribbean. This pattern, in part, may result from the increasing rates of deportation of children from Senegambia over time” (The American Journal of Human Genetics, 107, 265-277, August 6, 2020, p. 272). Similarly the article states that “Senegambia is underrepresented given the overall proportion of enslaved people who were deported from this region to the Americas. This is likely because Senegambia was one of the first African regions from which large numbers of people were enslaved” (The American Journal of Human Genetics, 107, 265-277, August 6, 2020, p. 272). So here we see how time of enslavement and who actually was enslaved at the time impacts representation amongst DNA segments.

Another important point is the import and then mixing of enslaved people once in the Americas: “It is unlikely that members of distinct African communities remained isolated from one another after they reached the Americas. However, based on limited marriage records of enslaved people, it is likely that communities from distinct Atlantic African regions initially remained isolated, but interbred later, which would lead to genetic evidence of post-transport mixing of African populations over generations” (The American Journal of Human Genetics, 107, 265-277, August 6, 2020, p. 274). This is something important to consider as we study our own DNA and consider the movement of enslaved Africans across the Caribbean, for example. One point they make to this is the higher overrepresentation of Nigerian ancestry is parts of the Americas which is due to the intra-American trading of enslaved people from the British Caribbean (The American Journal of Human Genetics, 107, 265-277, August 6, 2020, p. 274).

Their study for example was impacted by the restrictions on the Angolan DNA genotyped by 23andMe due to consent and privacy guidelines, which means that in the future this study can be expanded on as more samples and local populations become available to study.

Overall, I enjoyed reading the article and learned some more about the slave trade in the Caribbean/Americas and the genetic impact it left behind in our DNA. I found it interesting to read this study and then turn to my DNA and see how it affected what I inherited and which specific groups were more present in my DNA and that of my family. My hope is that as more of these studies come about and the more documentation become available, I am able to better piece together the information of my ancestors and hopefully find places in Africa where my family had originally come from. For example, one specific and tangible way is to find a female direct descendant of Eglantine Lautin and to test the maternal haplogroup to see what can be learned from that group and try to connect it with a tribe or modern day African country seeing as how Eglantine was directly brought to Martinique from Africa. You can read more in my post titled “Tracing Eglantine Lautin“.

I am excited for more explorations into this part of my DNA to ultimately learn more about myself and my past!

I just wanted to let you know that your article was very interesting. Also I read somewhere that you mentioned blanqueamiento. But it is misspelled. Many of the last names you mentioned are also in my genealogy. Wondering if we could be related. Thanks for sharing.

Hi Sandra, thanks for reading my blog! The 23andMe paper refers to racial whitening as “branqueamento” by its Portuguese word and since I drawing information from the study, I decided to keep the Portuguese version versus using “blanqueamiento”, its Spanish version. If your Marrero are from the Toa Alta/Corozal area, it’s very possible – my Marrero have been in those towns since at least the 1700s. -Luis

Read all the blogs and thanks for giving us such insightful experiences. I have been researching for 8 years both my husband and my own lines. I have done DNA testing in Family tree DNA, Ancestry, 23& me, My Heritage and Geneanet . Noted several Luis Rivera’s in Ancestry by the way ,LOL. My dad’s maternal line is rich with “Riveras”. I was planning to go to Puerto Rico in 2020 for genealogy research but Covid 19 interfered. I am so thankful when others upload digital records from the Island. Keep Blogging!