November in the United States honors “Native American History Month” and so I wanted to write up this post this month to overlap native indigenous roots in the United States with indigenous roots in Puerto Rico.

I want to showcase a document that in my opinion is fairly rare and that is because it contains information that is not super common in many genealogical records in Puerto Rico.

This post will focus on Josef (José) Linares and his death record which mentions he is an “indio de nación” (Nation Indian).

Social context

The Spanish arrival in the late 1400s to the island of Puerto Rico would ultimately be the main downfall of the Taíno on Boriquén given their contact with disease, slave labor, and later rebellions against these new people on their island. Despite this, a form of “hyper creolization” occurred on the island where the Spanish and Taíno quickly mixed, along with the Africans, to form the underlying basis of Puerto Rican-ness. This would become known as “las tres razas” (the three races) to which many (if not all old stock Puerto Ricans) carry in their DNA to varying degrees.

Many Puerto Ricans, for example, carry indigenous haplogroups such as A and C. A genetic study from 2001 demonstrate “Native American haplogroup frequency analysis shows a highly structured distribution, suggesting that the contribution of Native Americans foreign to Puerto Rico is minimal. Haplogroups A and C cover 56.0% and 35.6% of the Native American mtDNAs, respectively…Most of the linguistic, biological, and cultural evidence suggests that the Ceramic culture of the Taínos originated in or close to the Yanomama territory in the Amazon. However, the absence of haplogroup A in the Yanomami suggests that the Yanomami are not the only Taíno ancestors.” [1]

This is interesting to note because I myself carry the C maternal haplogroup while my maternal grandfather carries the A maternal haplogroup.

One of the most difficult parts of understanding the Taíno society is knowing their population numbers. Some argue there were anywhere between 20,000-50,000 indigenous people on the island when Columbus arrived [2] while I have also seen some higher numbers as well. Apparently, by 1530 when Manuel de Lando took a census of the island, only 1,148 Taíno were recorded living in Puerto Rico. [3]

This would mean that Taíno society would ultimately would be “wiped out” by the turn of the 17th century.

Genealogical Context

Given this social context, it is fairly difficult to trace our indigenous ancestors on paper. I have talked a bit about this topic before and mainly in regards to the word “pardo” and its definition when it comes to race on the island. You can read two posts here that might help to give you some more genealogical context of the word:

1. Race Among the “Ortiz Rivera” Siblings of Corozal

2. Manuel Ruiz – A Pardo Slave in the 1700s

As I have mentioned earlier, given the quick mixing in Puerto Rico some argue that the Taíno as a whole (both in society and identity) quickly vanished from the social scene of the island leaving behind the individuals who would ultimately become our ancestors, those who carried the legacy of the Taíno but who not fully identified as them.

This is why finding a document with the words “indio de nación” was surprising to see!

Document Context

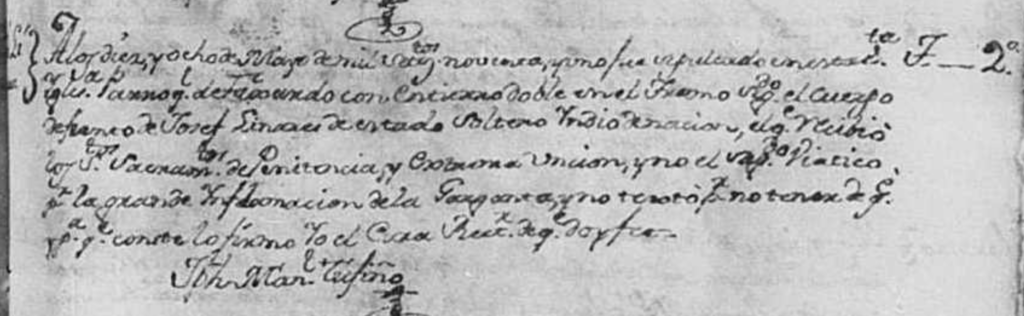

I was randomly searching around in the Fajardo records from the 18th century when I came across this record. Located in the second book of deaths ranging from 1789 to 1800 I was able to find a death entry for a man named Josef Linares.

The record states that he was single, an “yndio de nación” (Nation Indian), and he received the sacrament of penance and extremaunción (anointing of the sick) having died the 18th May 1791. However, it is interesting to note that it then states: “…y no el sag.do (sagrado) viático pr (por) la grande ynflamacion (inflamación) de la garganta” (and not the sacred viaticum given the big inflammation in his throat).

The viático known in English as the “viaticum” is a term used by “the Catholic Church for the Eucharist (also called Holy Communion), administered, with or without Anointing of the Sick (also called Extreme Unction), to a person who is dying; viaticum is thus a part of the Last Rites.” (Wikipedia).

Given the fact that Josef Linares was suffering from a big inflammation in his throat, he was unable to receive the eucharist though he was able to receive the sacrament. This is also important to note because it likely means that Josef either for all or partially some of his life was of the Catholic faith. There have been deaths where people were unable to get the sacraments since they were not Catholic and also people baptized on their deathbed and then given the last rites. So it’s interesting to see that he was given the Last Rites and the sacrament of penance on his deathbed.

"Indio de Nación"

A Google search for the term “indio de nación” brings up various tribes such as Zapotec, Tarasco, Chichimeca, amongst other tribes. It seems that the term was used to refer to indigenous people from their respect land(s); in this case the evidence would point to it being a native from the island of Puerto Rico. I can find no references to “indio de nación” tied specifically to Puerto Rico, so it might be that this term was not commonly applied or used on the island. From my genealogical searches the last odd 20 years this is definitely the case. Similarly, a search on PARES (Portal de Archivos Españoles) only brought up three hits for the exact term “indio de nación”, but here it could be a lack of digitized records or wide variations of this term.

What is interesting is how records such as these can help to reevaluate and hopefully rewrite the history we know of the Taíno. For centuries it has been believed that they were completely wiped out and with the advent of DNA testing, we can now see that it is not the case. Though a lot was lost of the Taíno during the conquest of the island the subsequent years, there is still a lot to be gained in terms of knowledge from our ancestors.

Conclusion

There is still a lot to understand about Josef Linares and the use of the term “indio de nación” in Puerto Rico. We do not know how old Josef was at his death and so we have no current leads for a baptism, though since there is no mention of him being a párvulo (infant) it is highly likely that he was considered “of age” by the time of his death meaning he could have been born as early as mid-1770s. We can see that Josef has the surname “Linares” a Spanish last name but we have no parent names as well. So for now it seems that Josef will be a dead end until either all Fajardo records are digitized or until someone else bumps into his baptism, the same way I have bumped into his death record.

It would also be interesting to see if this term can be found in other parts of the island and during what timeframe. So far, I have not seen it in use in any other town and in any other time period. Could there be more records from this time period in Fajardo that also name others as “indios de nación”? Only more research will tell!

Have you heard of the term "indio de nación" before?

Cover Photo: Iglesia Católica Santísimo Rosario (Fajardo, Puerto Rico), “Libro 2 Defunciones 1789-1800,” pg. 17, last entry, Josef Linares, death, 18 May 1791; accessed as “Registros Parroquiales, 1854-1942,” browsable images, FamilySearch, (https://www.familysearch.org/search/catalog : accessed 5 November 2023)

[1] “Mitochondrial DNA analysis reveals substantial Native American ancestry in Puerto Rico”, National Library of Science (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11512677/ : accessed 5 November 2023).

[2] “History of Puerto Rico”, Britannica (https://www.britannica.com/place/Puerto-Rico/History : accessed 5 November 2023).

[3] “Genocide Studies Program – Puerto Rico”, Yale University (https://gsp.yale.edu/case-studies/colonial-genocides-project/puerto-rico : accessed 5 November 2023)